Beyond Single Numbers: How Confidence Intervals Strengthen Product Analytics

Carlos, a Senior Product Manager at our fictional FinPilot, had spent months refining an AI-driven onboarding flow for financial advisors. After launch week, he checked the metrics:

- 80% of users completed onboarding.

- 90 seconds average time on task.

- 72 on the System Usability Scale (SUS).

On the surface, it looked like a major success. But in the sprint review, Lena, the UX Researcher, asked a crucial question:

“How sure are we that 80% of users actually complete onboarding? Without confidence intervals, we don’t know if 80% is rock-solid—or just luck.”

It’s easy to see one statistic—“80% completion,” “4.2-star rating,” “72 on SUS”—and treat it as fact. But these are point estimates, shaped by sample size, random variability, and sampling method. As Jeff Sauro & Lewis (2016) emphasize, no UX metric exists in a vacuum; every number carries uncertainty.

Try Userpilot Now

See Why 1,000+ Teams Choose Userpilot

What is a confidence interval? A straightforward definition

A confidence interval (CI) is a range that expresses how precise—or uncertain—you are about a metric. Instead of saying;

“80% of users completed onboarding”

A more statistically sound statement would be:

“We estimate 80% completion, but the true rate is likely between 65% and 92%.”

That second statement is far more trustworthy because it acknowledges the margin of error.

👉🏻 Important note: A 95% confidence interval doesn’t mean there’s a 95% chance the true number is within the range. Instead, it means that if we repeated the test 100 times, 95 of those confidence intervals would contain the true value (Sauro & Lewis, 2016).

Do you trust your product metrics too much?

A single number like “80% completion” often hides the truth. Take this 4-step assessment to see if your product analytics rely on confidence intervals or just luck.

The business impact of misunderstanding confidence intervals

What happens when leadership assumes a single UX metric is exact?

🚨 Risk #1: They invest prematurely based on incomplete data.

🚨 Risk #2: They treat estimates as hard numbers, missing the real range of outcomes.

“If you present a single figure as exact—like 80%—leadership might invest prematurely,” write Sauro & Lewis (2016).

“A confidence interval communicates the risk by showing upper and lower bounds.”

In essence, confidence intervals don’t just improve UX research—they prevent costly mistakes at the business level.

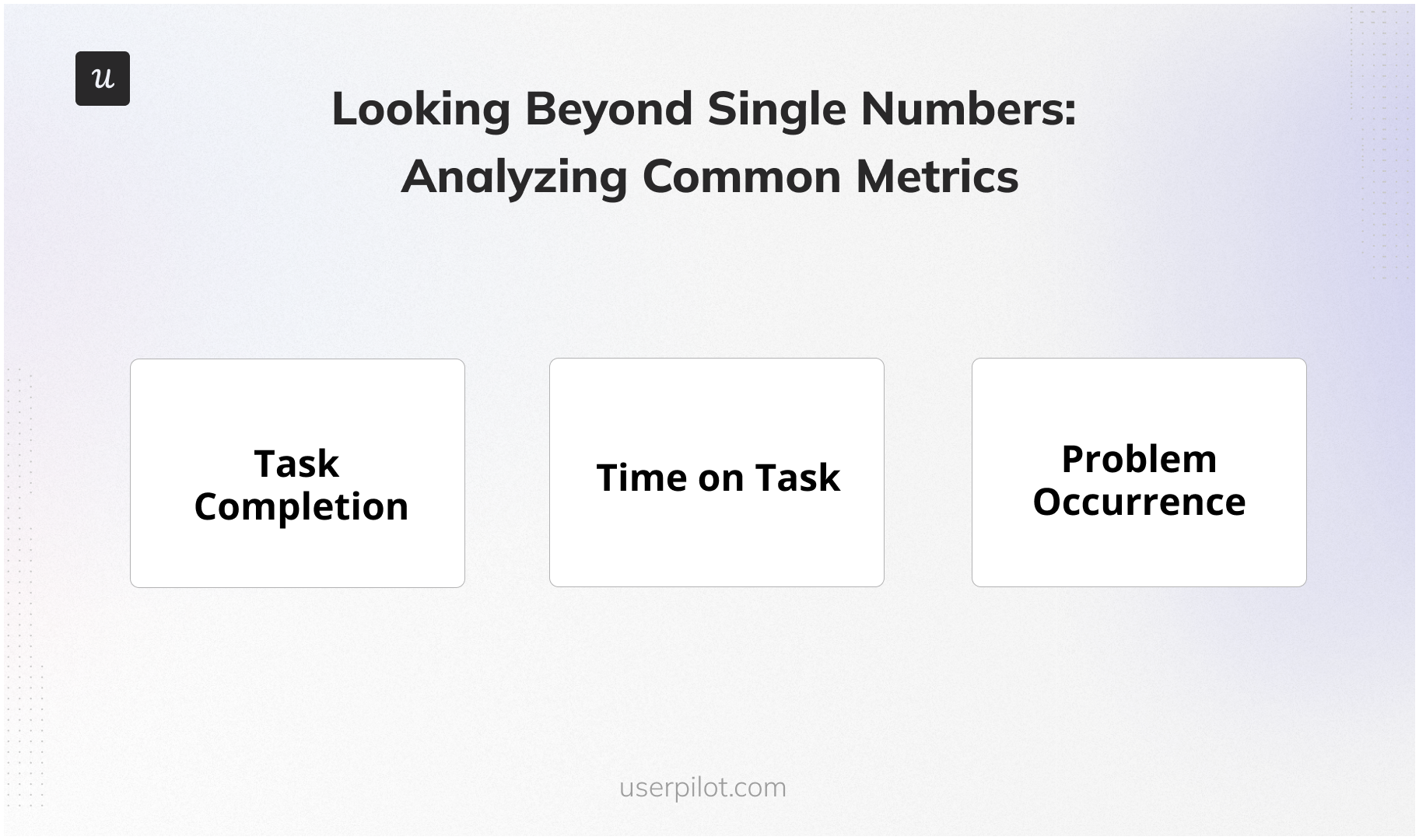

I’ll explore three common metrics, highlighting the issues with relying on single numbers and how confidence intervals can be calculated and interpreted for each.

Scenario 1: task completion – “80% success? Are we sure?”

Carlos’ story: The account verification roadblock

Carlos’s team had worked hard to simplify FinPilot’s account verification process. A usability test with 15 participants produced promising results:

✔ 12 out of 15 users successfully verified their account → 80% completion rate

The team was ready to declare success—until Lena, the UX Researcher, raised a critical concern:

“With a sample of just 15 users, even one or two different outcomes could swing our reported completion rate from 80% to anywhere between 73% and 87%. We need to check the confidence interval.”

Going deeper: Adjusted-Wald for task completion

Jeff Sauro & Lewis (2016) emphasize the importance of using the adjusted-Wald method for small sample sizes, especially for binary success/fail metrics:

“The adjusted-Wald interval is recommended for smaller sample sizes, especially for binary metrics near 0% or 100%.”

Why adjusted-Wald?

- Small sample sizes (n < 30) lead to unstable estimates.

- Binary metrics (success/failure) are highly sensitive to individual outcomes.

- The Adjusted-Wald method stabilizes the estimate by adding “virtual” successes and failures, preventing extreme confidence intervals.

👉🏻 Important note: While the Adjusted-Wald method is ideal for small samples, larger usability tests (e.g., n > 50) may yield similar results using standard Wald or Wilson intervals without needing adjustments (Sauro & Lewis, 2016).

Steps to calculate the confidence interval

- Adjust the proportion → Add 2 “virtual” successes and 2 failures to correct small-sample bias.

- Calculate the standard error (SE) → Measures variability in the adjusted proportion.

- Find the margin of error (MOE) → Multiply SE by a statistical Z-value.

- Compute the confidence interval (CI) → Adjusted proportion ± MOE gives the range.

📌 Formula overview: CI = Adjusted Proportion ± (Z-value × SE)

Interpreting confidence interval for task completion in product analytics

✅ Show the range (not just a single number!)

Instead of: “80% of users completed onboarding.”

Say: “Estimated 80% (CI: 55%–92%).”

Why? A single percentage can be misleading—confidence intervals help stakeholders understand the certainty behind a metric. If the lower bound is 55%, leadership might rethink a premature rollout.

✅ Compare multiple variants (overlap means no clear winner)

A/B testing without confidence intervals can lead to false conclusions. If two feature variations have overlapping CIs, their performance isn’t statistically different.

Why? Instead of declaring Version B is better than Version A, confidence intervals show if the difference is meaningful—or just random chance.

🚀 What to do instead? Gather more data, segment users, or refine the experiment before assuming an improvement.

✅ Gather more data if your CI is too wide

A confidence interval of 30%–95% is too broad to be useful for decision-making. If your range is too wide, the data isn’t precise enough to act on.

Why? A wider confidence interval means higher uncertainty. To increase precision:

- Collect more data points.

- Improve sampling methods.

- Reduce measurement noise.

🚀 Takeaway: If the lower bound is too low (e.g., 45% instead of 72%), it’s too early to make decisions—keep testing.

Scenario 2: Time on task – “120 seconds? Not so fast”

Carlos’ story: The checkout optimization trap

Carlos’s team had just redesigned FinPilot’s premium checkout flow to make the process faster and more seamless. Early data suggested a positive result:

✔ Average checkout time: 120 seconds

✔ 15% fewer drop-offs

Carlos was ready to announce the checkout experience had improved significantly. But Lena, the UX Researcher, cautioned:

“An average of 120 seconds doesn’t tell the whole story. What if some users took 300 seconds while others finished in 60? We need to check the full distribution.”

This matters because:

- A single average doesn’t show variability.

- If a few users take an unusually long time, the mean can be artificially high.

- The confidence interval tells us whether this “improvement” is real—or just statistical noise.

Carlos realized that without confidence intervals, they might misinterpret the results—and overestimate the success of the checkout redesign.

Going deeper: Time on task and log-transform with T-distribution

Jeff Sauro & Lewis (2016) explain:

“Time data often follows a lognormal distribution, so using a geometric mean or log-transformed data will provide more accurate confidence intervals.”

Why use log-transform for time data?

- Time-on-task data is typically skewed—a few slow users can pull up the mean.

- A log transformation normalizes the data, reducing the impact of outliers.

- T-distribution is better than the normal distribution for constructing confidence intervals with small sample sizes (<100).

👉🏻 Important note: For larger sample sizes (n ≥ 25), the arithmetic mean becomes a more reliable estimator, as the impact of extreme values diminishes due to increased data stability. While log transformation still helps normalize skewed distributions, the difference between using a geometric mean and an arithmetic mean becomes negligible.

Steps to calculate the confidence interval

- Convert each time value to log-time → Apply the natural logarithm (ln) to reduce skewness.

- Find the mean and standard deviation of log-times → Measure the average and variability.

- Compute the confidence interval in log-space → Use a T-distribution for small samples.

- Convert back to seconds → Exponentiate the bounds to interpret them in real-time.

📌 Formula overview: CI = e^(Log-Mean ± (t-value × SE))

Interpreting confidence interval for time on task in product analytics

✅ Pre/post comparisons: Look at CI overlap

Before declaring a checkout speed improvement, check confidence intervals. If the old and new checkout times overlap significantly, there’s no statistical evidence of a meaningful improvement.

Why? Even if the new design’s average time is lower, overlapping CIs indicate that the observed difference might be due to randomness rather than a true speed boost.

🚀 What to do instead? Instead of assuming success, test with a larger sample to reduce variability—or analyze specific user segments for real performance changes.

✅ A/B Tests: detect meaningful differences

Comparing two checkout flows? Confidence intervals reveal whether the difference is real or just noise.

Why? If Version A and Version B have overlapping confidence intervals, you cannot claim one is faster than the other.

🚀 What to do instead?

- Increase sample size to refine estimates.

- Segment users by behavior (e.g., first-time vs. returning customers).

- Look at other performance metrics beyond average task time.

✅ Segmenting the extremes: spot UX issues

Not everyone takes the same amount of time—so check outliers. Some users might take 2–3x longer than average. These cases can reveal critical UX friction points.

Why? Long checkout times don’t always mean slow users—they might signal usability issues.

How to investigate?

- Heatmaps: Identify hesitation points, confusing CTAs, or bottlenecks in the flow.

- User segmentation: Compare time-on-task for new vs. returning users to see where friction occurs.

- Session replays: Watch individual user interactions to pinpoint slowdowns.

🚀 Takeaway: If the confidence interval suggests variability, use behavioral analytics to understand why some users struggle—and fix the real bottlenecks.

Scenario 3: Problem occurrence – “3 out of 5 struggled. 60%?”

Carlos’ story: The confusing portfolio screen

Carlos’s team tested a new “portfolio allocation” screen with five financial advisors. The results: 3 out of 5 users encountered a UI issue → 60% problem rate

“That’s huge.” Carlos said, but Lena, the UX Researcher, pushed back:

“It’s only 5 people. A single different outcome would shift the rate by 20%. Let’s calculate a confidence interval.”

This matters because binary usability issues (users did or didn’t encounter a problem) suffer from extreme fluctuations in small samples. Without a confidence interval, reporting a “60% struggle rate” could mislead stakeholders into overestimating—or underestimating—the severity of the issue.

Going deeper: Adjusted-Wald for problem occurrence

Once again, adjusted-Wald is the go-to method for small binary datasets (Sauro & Lewis, 2016).

- Tiny samples (n=5) lead to big swings → A single different outcome could shift the result by ±20%.

- Avoids misleading extremes → Instead of assuming exactly 60%, Adjusted-Wald smooths the estimate, preventing false confidence in small-scale results.

- More reliable decision-making → Helps determine whether an issue is likely to impact a broad user base or just a few testers.

Interpreting confidence interval for problem occurrence in product analytics

✅ Prioritize fixes based on confidence intervals

Not every reported issue is equally urgent. Confidence intervals help determine whether a problem affects enough users to warrant an immediate fix.

- High lower bound (e.g., 40–50%)? The problem is statistically significant and likely affects a large portion of users. Prioritize a fix.

- Low lower bound (e.g., 10–20%)? The issue might be less severe or just a statistical fluctuation—additional testing may be needed before committing resources.

🚀 What to do instead? Align issue prioritization with the severity indicated by the confidence interval, rather than treating all reported problems equally.

✅ Communicate uncertainty to stakeholders

UX and product teams often need to explain the issue’s severity to leadership. Instead of a single number, confidence intervals present a more transparent, risk-aware view.

Instead of: “60% of users had issues with the portfolio screen.”

Say: “Estimated 60%, but the true rate is likely between 25% and 87%.”

Why?

- Leadership gets a clearer understanding of potential risk.

- Teams can plan mitigations based on worst-case scenarios rather than assuming a misleadingly precise number.

🚀 What to do instead? In UX reports, dashboards, and presentations, always display confidence intervals alongside issue rates to set realistic expectations.

✅ Quantify improvements, not just fixes

Fixing an issue is one step—measuring whether it was actually solved is another. Confidence intervals help confirm whether post-fix improvements are meaningful.

- Common mistake: Declaring a fix successful based on anecdotal feedback or a small shift in percentages.

- Better approach: Compare pre-fix and post-fix confidence intervals to see if the issue rate has genuinely decreased.

🚀 What to do instead?

- Expand testing to increase sample size.

- Refine the fix if CIs show no meaningful change.

- Segment results to see if certain user groups still experience the issue.

Summary table of methods

| Scenario | Metric Type | Recommended Method | Reason |

| 1. Task Completion | Binary (Success/Fail) | Adjusted-Wald CI (Sauro & Lewis, 2016) | Adds “virtual” successes/fails, stabilizing small-sample estimates |

| 2. Time on Task | Continuous (often skewed) | Log-Transform + t-Distribution (Sauro & Lewis, 2016) | Time data follows a lognormal distribution; t-distribution handles small n |

| 3. Problem Occurrence | Binary (Issue/No Issue) | Adjusted-Wald CI (Sauro & Lewis, 2016) | Small sample volatility requires correction, same reason as Scenario 1 |

Final thoughts: Confidence intervals as your product compass

Carlos realized just how fragile a single number—like “80% success” or “4.2 rating”—can be if you don’t account for uncertainty. Confidence intervals provide the context behind the numbers, guiding whether you need more data, a cautious pilot, or a full-scale rollout.

References: 📖 Sauro. J., & Lewis, J. R. (2016). Quantifying the user experience: Practical statistics for user research (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: Morgan-Kaufmann.

Don’t Miss Out on Expert Knowledge That Keeps You Ahead.