When user stories are written well, they clarify the problem, highlight the user’s goal, and keep everyone aligned on the outcome instead of the feature request. When they’re written poorly, they turn into vague placeholders that create confusion, slow teams down, and lead to work that doesn’t deliver real value or improve adoption.

TL;DR: In this guide, you’ll learn what a user story actually is, how to create user stories that move the needle, and how to avoid the traps that lead to bloated backlogs and misaligned releases. I’ll also provide practical user story examples you can adapt for your own product, along with the exact steps I use when shaping stories with cross-functional teams.

What is a user story?

User stories describe a feature or capability from the end user’s perspective, focusing on what they need and why it matters.

It’s not a technical specification or a software feature written in technical terms. I treat it more as a prompt that helps the team stay focused on user needs and the product value we intend to deliver.

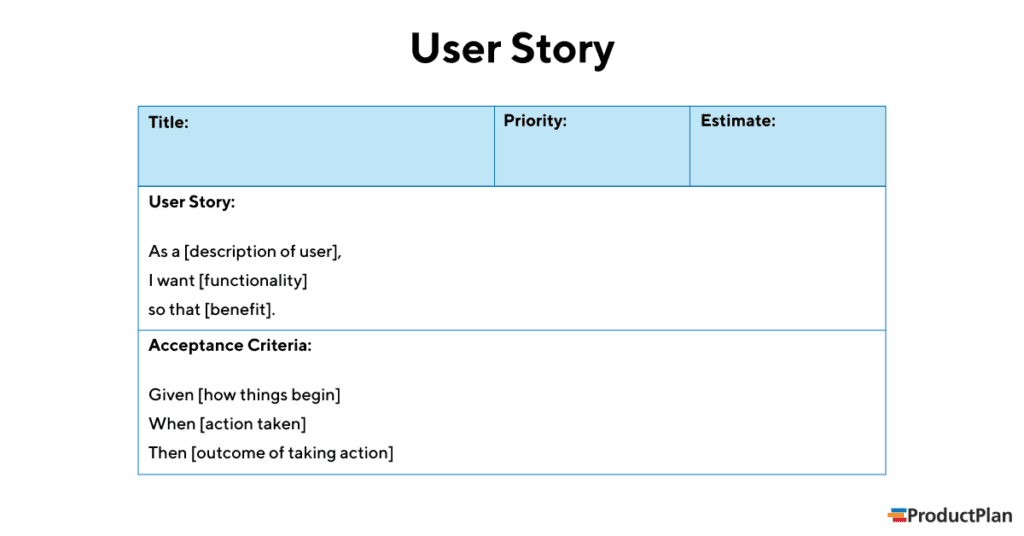

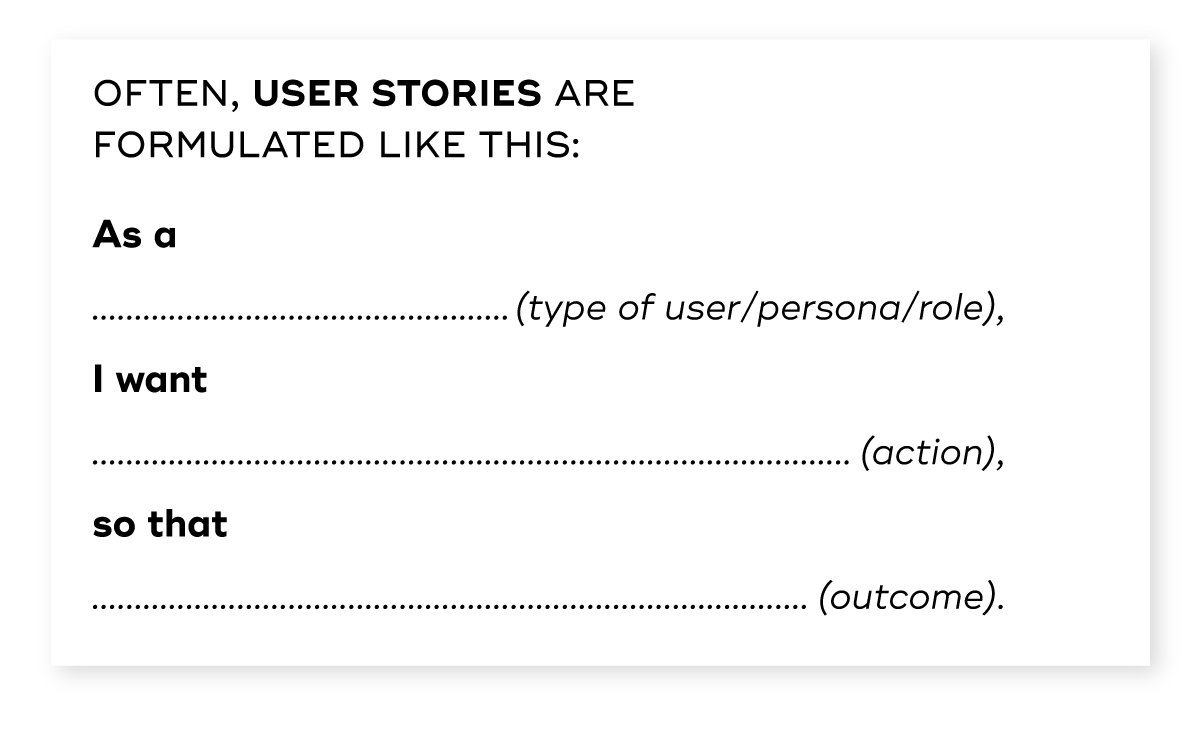

User story template

The typical user story consists of three parts woven into a simple template:

As a <role>, I want <feature or action>, so that <benefit or value>

Here is what each part represents in practice:

- Role: Identify the person you’re building for. Avoid vague labels such as “users.” A clear role helps the development team picture a real person, whether that’s a product manager, a founder, a new user, or an experienced account holder.

- Action: Describe what the person wants to do. Keep the focus on user intent rather than the method of building it. For example, instead of saying the system should generate segmented lists with a new filtering engine, write it from the user’s point of view as wanting to filter their dashboard data to review only the accounts that need attention.

- Benefit: Explain why the action matters. This connects the request to the value it creates. If the role you named above wants to complete the action you described, the benefit should clearly show why that action supports their goals. For example, a product manager using an analytics tool might want to filter their dashboard data because it helps them spot churn risks early and decide which accounts need outreach before renewal.

Why user stories matter for PLG teams

User stories force you to avoid overengineering solutions before you even understand the problem. Here are three reasons why PLG teams should create user stories:

- They keep the focus on the user: It’s easy to get lost in the technical weeds. “We need to add a column to the SQL database” is a technical task. “As a marketing manager, I want to segment my users by industry so I can send relevant emails” is a user story. The latter keeps customer empathy at the center of the development process.

- They encourage collaboration: Since user stories are written in plain English, everyone can understand them. Stakeholders, designers, developers, and testers can all discuss the same story. This shared understanding reduces the risk of product failure caused by miscommunication.

- They define “done” based on value: A feature isn’t done when the code is written. It’s done when users adopt it, and the work delivers business value. By clearly stating the “So that” part of the formula, you define what value realization looks like for that specific task.

The 3 Cs of agile user stories

A common misunderstanding in product teams is the idea that the text written on a Jira ticket is the full requirement. It isn’t. Ron Jeffries, one of the creators of Extreme Programming, described a user story as three connected parts known as the 3 Cs. These parts help teams avoid treating the story as a fixed document and instead use it as a tool for shared understanding:

1. Card

The card contains a brief written description of the story. It’s the familiar “As a… I want… so that…” line we covered in the previous section.

This isn’t meant to contain every detail. It serves as a clear reminder of the need, something that anyone can recognize at a glance.

2. Conversation

This is where most of the real work happens. The story on the card invites a discussion between the agile team, the product owner, and other key stakeholders.

During the conversation, each team member helps explore the problem, uncover edge cases, clarify constraints, and surface creative solutions before the team decides on the most reasonable approach.

These discussions also help you refine user needs and confirm that you’re solving the right problem before anyone writes a line of code.

3. Confirmation

The final part is the set of acceptance criteria that confirm whether the story is complete. These criteria outline the conditions that must be met for the story to deliver the expected value. They also help prevent misunderstandings during development because they describe what success looks like in concrete terms. When the criteria are written clearly, your team can test the story with confidence and know that the user’s goal has been met.

Together, the 3 Cs turn a user story into a collaborative workflow rather than a static piece of documentation.

Step-by-step process for writing great user stories

Writing a user story is easy. Creating a good user story that leads to a successful feature takes effort. Here is the process I use:

1. Validate the need

Before adding anything to the backlog, make sure the problem is real. This early alignment keeps your team focused on work that solves a genuine issue rather than a guess or a loud internal request.

One reliable way to validate a need is to start with patterns you notice in support tickets or user feedback. For example, you might see repeated complaints from new customers who say they can’t complete a key onboarding step. Don’t treat these reports as enough on their own. Confirm the pattern in your analytics so you don’t end up building a feature for a tiny portion of users when the issue could be solved with a simple tooltip.

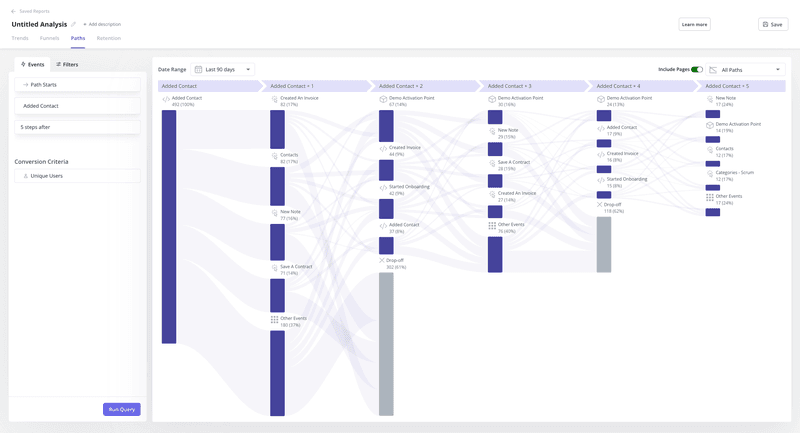

In your analytics tool, review funnel or user path reports to see how many users drop off at that step and where the friction begins.

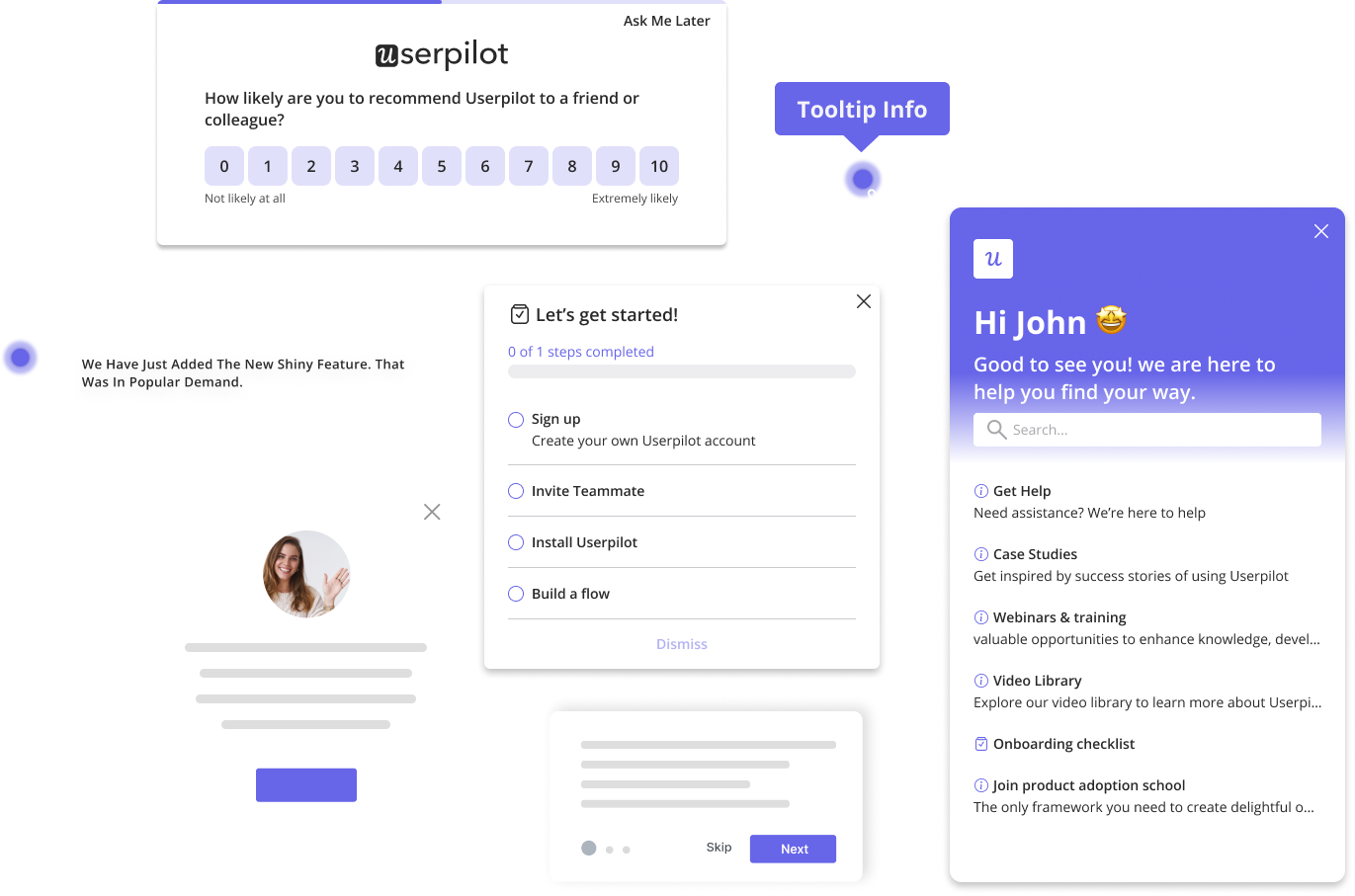

Userpilot helps with this stage by showing you exactly where users struggle. Its funnel, cohort, and path analysis features reveal where customers pause, backtrack, or abandon a flow.

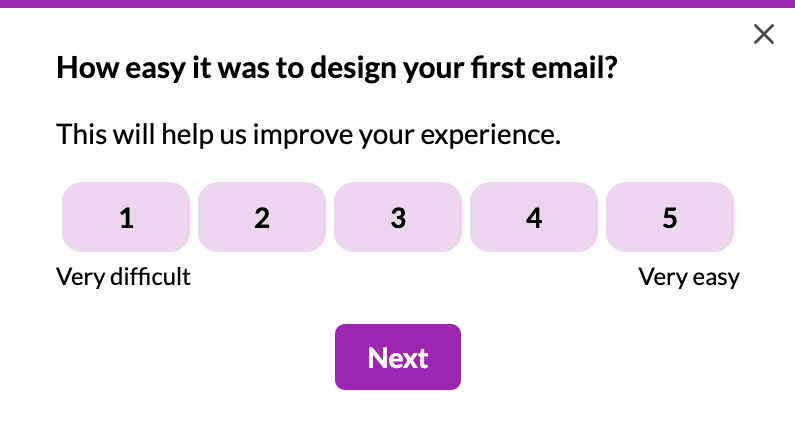

When you need direct input from users, you can trigger surveys inside the product, by email, or in your mobile app to gather feedback from the people who experience the problem.

This mix of quantitative and qualitative insight gives you confidence that the story you’re about to write reflects real user behavior and not assumptions.

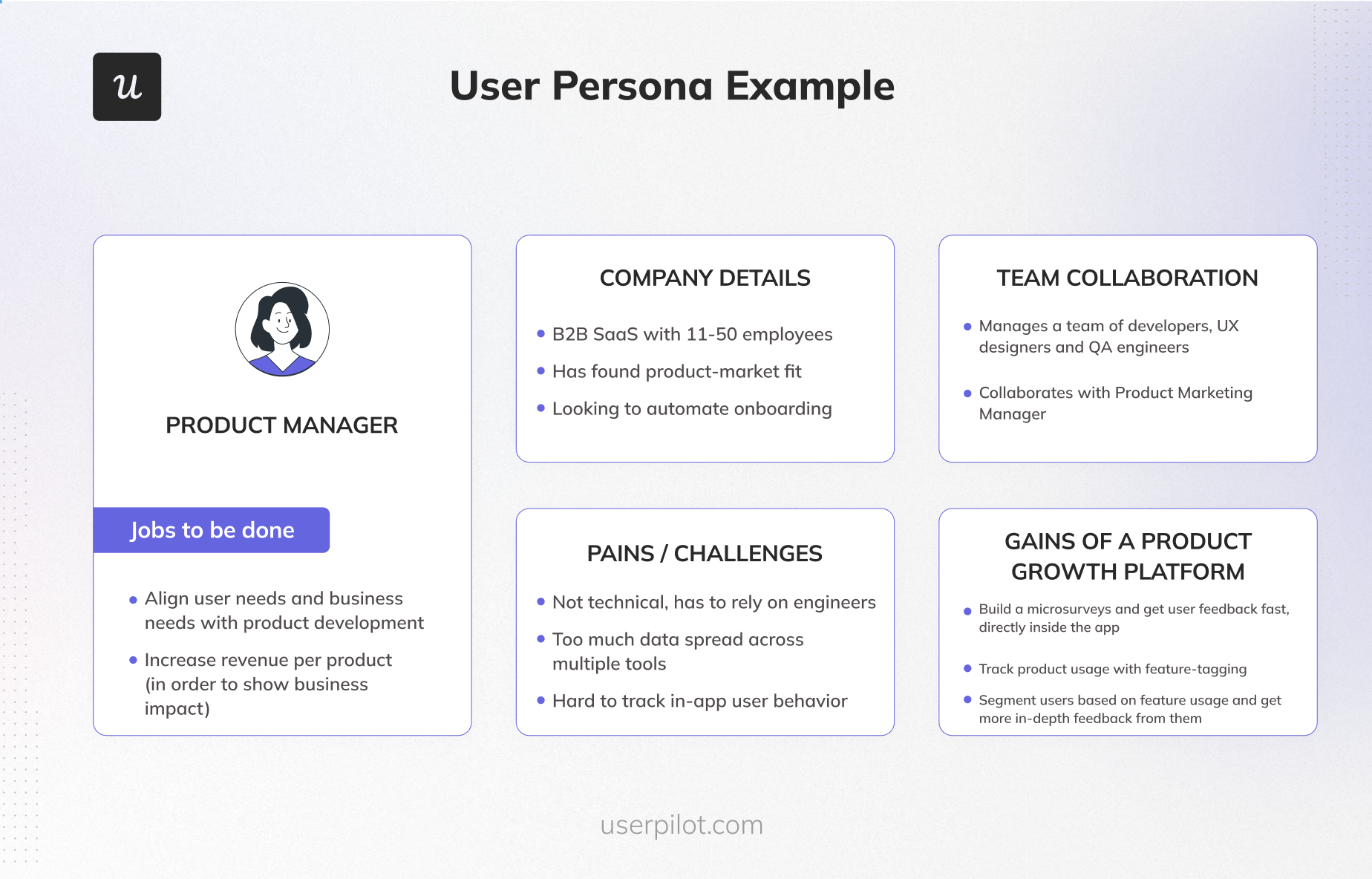

2. Identify the specific persona

Once you’ve confirmed the problem is real, the next step is to pinpoint exactly who experiences it. In B2B SaaS, the buyer, the admin, and the daily end-user typically have different goals, mental models, and definitions of value. A clear persona keeps the story anchored to the main user’s workflow rather than a blend of several viewpoints that would result in a vague or conflicting requirement.

Start by reviewing who encountered the problem during your validation step. Look at support conversations, survey responses, and usage data to see which roles appear most often. For example, complaints about billing accuracy usually come from finance or operations, while feedback about navigation or shortcuts tends to come from power users who spend several hours a day inside your product. This helps you avoid blanket labels that don’t guide any meaningful decision during development.

Here’s a user persona example you can adapt to cover key details about your target audience:

3. Draft the narrative

Write the statement using the classic format, but ensure you’re adding context, not just words.

A weak story usually comes from a lack of detail. Something like “As a user, I want search to find things” doesn’t guide anyone. It doesn’t say who’s searching, what they’re looking for, or why the speed or accuracy of the result matters.

A stronger version names the role, the intent, and the reason in concrete terms. For example, “As a customer service rep, I want to search by email address so I can find orders quickly while on the phone with a customer.” This gives the development team a clear direction. It suggests the need for fast lookups, error handling for mistyped emails, and a layout that works during live conversations.

Remember, at this stage, you’re not deciding on the solution. You’re describing the situation from the user’s perspective, so the development team can make informed choices when exploring how to solve the problem.

4. Set the acceptance criteria

Acceptance criteria are the specific conditions that the software system must meet to deliver the value you promised in the narrative. They remove guesswork by spelling out what success looks like in a way that both product and engineering can understand and test.

When I write the criteria, I like to use a simple form of Gherkin syntax. It uses three parts to structure how the feature behaves in a specific situation:

- Given to describe the starting state or precondition.

- When to describe the action the user takes.

- Then to describe the outcome you expect to see.

This structure forces you to think in terms of behavior that can be tested rather than vague expectations such as “works as expected.”

Here’s a practical example for a login story in a SaaS product:

Scenario 1: Successful login

- Given the user is on the login page and they have an active account.

- When they enter a valid email and password.

- Then they are redirected to the dashboard, and they remain logged in when they refresh the page.

Scenario 2: Invalid password

- Given the user is on the login page.

- When they enter a valid email with an incorrect password.

- Then the system shows a clear error message that says “Invalid credentials.” The password field is cleared while the email remains filled, and the user can retry immediately without reloading the page.

Scenario 3: Locked account after multiple failures

- Given the user has entered an incorrect password five times in a row.

- When they attempt to log in again.

- Then the account is temporarily locked. The user sees a message that explains what happened and how to unlock their account.

By writing acceptance criteria in this format, you turn a short narrative into a set of concrete behaviors that developers can implement, testers can verify, and stakeholders can understand.

5. Estimate and slice

Since most sprints last two to three weeks, each story needs to be small enough to start and finish within that window.

A story with multiple moving parts is usually too big to move through design, development, testing, and review in a single sprint. Such a story needs to be sliced into smaller user stories based on the value it delivers to users, often producing several related user stories that can each be completed within a sprint.

Let’s consider a simple example using a search feature. If you try to deliver the full search experience in one story, you’ll end up with something large and slow to ship. Instead, look at the different levels of value a user could receive from each slice.

- Story A: Search by exact order ID. This delivers immediate utility and gives users a working search tool.

- Story B: Search by customer name. This expands the usefulness of search and supports more real-world scenarios.

- Story C: Add fuzzy matching or autocorrect. This improves accuracy and feels more polished.

Notice how these smaller stories stand on their own, deliver clear benefits, and help the team ship value sooner. This approach keeps your work manageable and reduces the chance of carrying unfinished stories from one sprint to the next.

6. Track adoption

Many teams close a Jira ticket at deployment, but that only confirms the software exists. It doesn’t confirm that it’s used or that it solves the problem you validated in the first step.

This is where adoption tracking comes in. Once a story reaches production, monitor how many users interact with the feature, how often they return to it, and whether the behavior matches your expectations.

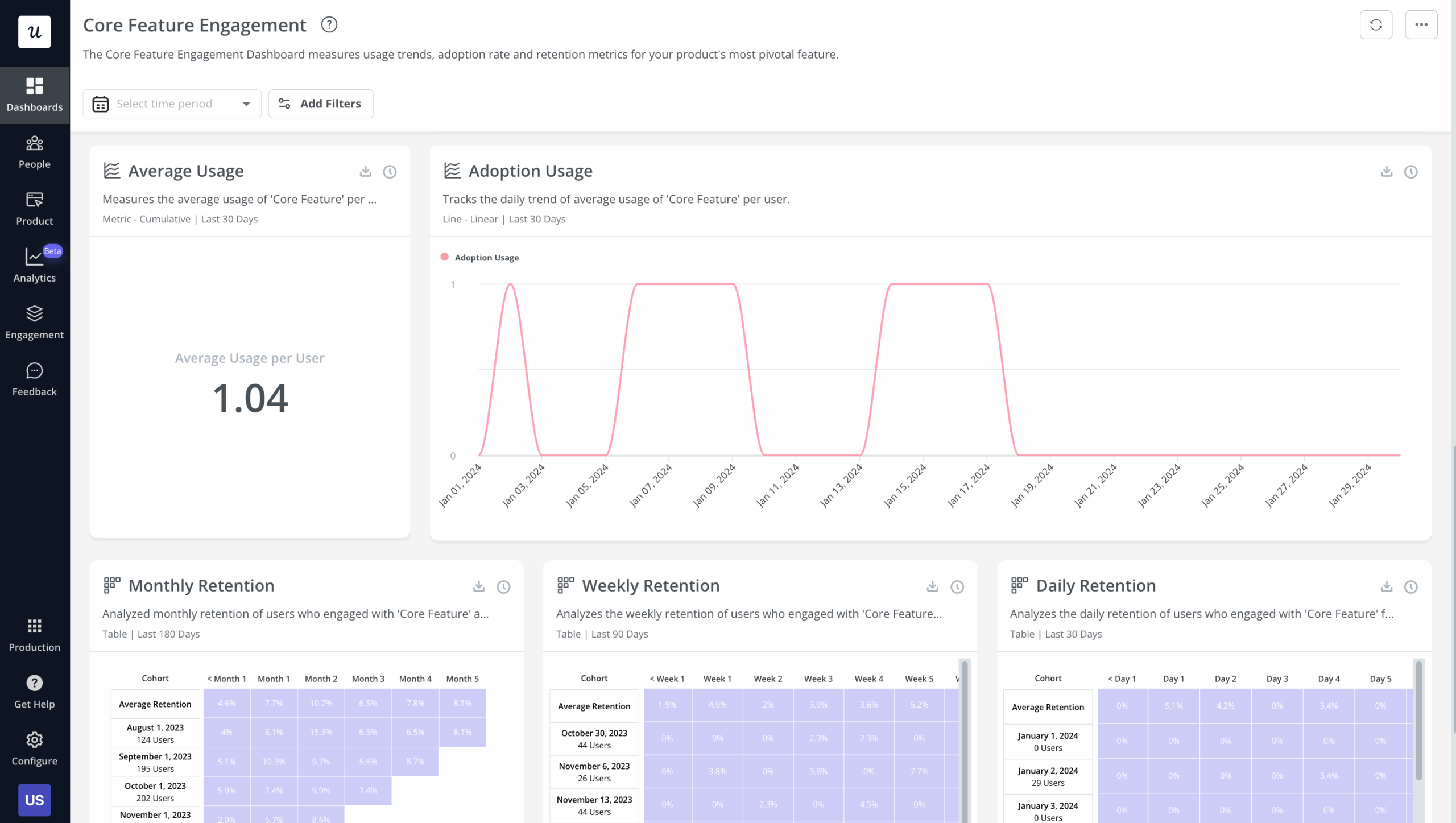

Userpilot helps you measure this through several analytics views. In the engagement dashboard, you can see metrics such as average usage per user and day-by-day adoption trends for a specific feature. These charts show whether engagement spikes, stays steady, or drops off after release. If adoption stalls, it may signal that users aren’t aware of the feature or that the workflow needs refinement.

The dashboard also includes retention tables that show how many users come back to the feature over weekly or monthly intervals. This helps you verify that the story solved a real problem rather than creating one-time curiosity. When retention is low, you can pair this data with path analysis or funnels to see where users get stuck or where they abandon the flow.

SaaS user story examples

To make the steps above more concrete, I’ve put together a table of good and bad user story examples so you can see what works and what doesn’t in real SaaS scenarios.

| Scenario | Bad user story ❌ | Why it’s bad | Good user story ✅ | Why it works |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 📊 Analytics dashboard | “As a manager, I want a dashboard to see everything.” | “Everything” guarantees scope creep. It’s an epic, not a story. | “As a Sales Manager, I want to see a graph of daily lead volume so I can spot dips in team performance immediately.” | Defines one insight and one output. The team can build a single chart and deliver value quickly. |

| 🧹 Managing technical debt | “Refactor the code.” | Sounds like internal busywork with no user or business value. | “As a Developer, I want to refactor the auth module so we can support SSO integration next quarter without rewriting the system.” | Frames clean-up as an enabler for an upcoming initiative, making it easier to prioritize. |

| 🆕 Feature onboarding | “As a user, I want onboarding to be clearer.” | Too vague. Gives no direction and can’t be tested. | “As a new trial user, I want an in-app checklist that guides me through creating my first project so I can start using the workspace without confusion.” | Defines who needs help, what they need to do, and why it matters for activation. |

| 💳 Billing and payment | “As a customer, I want better billing.” | “Better” doesn’t explain the problem or the value. | “As a Finance Manager, I want to download all invoices for a billing period in one file so I can complete monthly reconciliation faster.” | Addresses a clear workflow and ties directly to efficiency. |

| 💬Collaboration features | “As a user, I want comments.” | Doesn’t clarify who’s collaborating or why. | “As a Project Owner, I want to mention teammates in task comments so I can get faster responses without switching tools.” | Links the feature to a real motivation and a measurable workflow improvement. |

| 🔍 Search experience | “As a user, I want search to work better.” | “Better” is subjective and untestable. | “As a Support Agent, I want to search customers by email so I can pull up their orders quickly during live calls.” | Gives a clear input, output, and business reason tied to customer experience. |

Turn user stories into product impact

Strong user stories keep your team focused on real problems, clear outcomes, and value that users can recognize as soon as they try a feature. When each story begins with a validated need, names a specific persona, and includes testable acceptance criteria, you reduce guesswork and make every sprint more predictable.

As you start applying the ideas covered in this guide, it helps to have a platform that supports every stage of the process. Userpilot lets you validate needs with product analytics, see how users move through the user journey, measure adoption after release, and gather direct feedback from the people who experience each story

Ready to see Userpilot in action? Book a demo to get started.