If you spend five minutes on Reddit threads r/ProductManagement or r/agile, you’ll see PMs and devs saying the same thing: “Our user stories are useless.”

As a UX researcher, that hurts more than I’d like to admit, because you and I both know user stories are supposed to do something very different.

At their best, they’re the output of discovery and the input into design. They should frame a clear problem from the user’s perspective, not a mini requirements document.

So in this guide to user story templates for PMs, I want to help you fix that.

I’ll walk you through practical user story templates, show you how to plug user insights into them, and share concrete user story examples.

What are user stories?

A user story is a small, focused description of what a user needs and why that need matters.

Not what the feature is. Not how we’ll build it.

Just what the user is trying to do and the outcome they care about.

Most teams overcomplicate this. But a good user story is basically a reminder to build the right thing by grounding the work in a real user problem.

A user story template

Here’s the easiest way to think about it:

A user story = a problem + a user + a goal.

That’s it.

Imagine you’re building a task management tool. One of your users is a freelancer juggling multiple client deadlines. She often forgets to follow up on smaller tasks because there’s no way to prioritize or set due dates. To solve this, you define a user story: “As a freelancer, I want to set deadlines for tasks so I can manage my workload better.”

Why write user stories?

User stories help you focus on outcomes instead of output. They give you a simple way to connect product decisions with real user needs without getting lost in technical details or internal assumptions.

At their best, user stories serve as both communication tools and decision anchors. They help teams understand what to build and why it matters.

When you use a clear user story template, it becomes easier to align teams, define acceptance criteria, and prioritize features that solve actual problems.

They also build a shared understanding, reducing back-and-forth during sprint planning. Expressing user stories through conversation also reveals gaps that written templates might miss. It makes the process more collaborative and grounded.

The 3 Cs of user stories

A user story is not a specification document. It is a promise to have a conversation. Ron Jeffries, one of the founders of Extreme Programming, defined the “3 Cs” to keep teams from getting bogged down in documentation.

Card

The card is where every user story begins, whether it’s a sticky note on a whiteboard or a Jira ticket. It holds enough detail to capture the user’s goal, without overwhelming the team with early specifics.

In early stages, you might jot down ideas using sticky notes in Miro or Figma during team brainstorming. These visual tools help you sketch out quick story templates without overthinking structure.

The format should be simple enough to fit on an index card: a user + a goal + a reason. That keeps the focus on the end user’s perspective and not feature checklists or technical jargon.

Below is a user story card in a Miro board with sticky notes grouped by customer journey stages.

Conversation

Writing the user story is just the starting point. The details come out during discussions between the product owner, researchers, and developers. These conversations help clarify unknowns, resolve blockers, and shape the story based on the user’s perspective.

Expressing user stories through conversation also reveals gaps that written templates might miss. It makes the process more collaborative and grounded.

Confirmation

How do we know when we are done? This is where you need acceptance criteria. These are the specific conditions that the software must meet to be accepted by a user. I will cover how to write these later in the article.

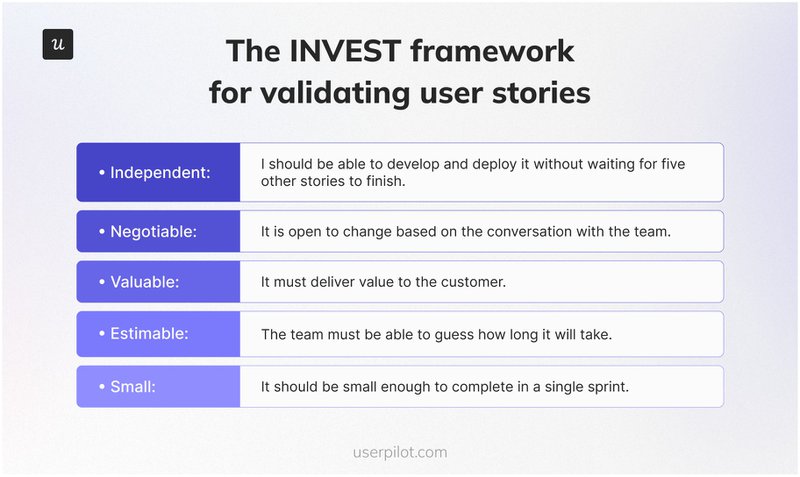

The INVEST framework for validating user stories

Before I hand a story over to the dev team, I run it through the INVEST checklist. If a story doesn’t hold up, it’s usually better to rewrite it or split it into smaller user stories.

- Independent: The story should be self-contained. I should be able to develop and deploy it without waiting for five other stories to finish.

- Negotiable: It is not a contract. It is open to change based on the conversation with the team.

- Valuable: It must deliver value to the customer. If I can’t link it to customer value, I cut it.

- Estimable: The team must be able to guess how long it will take. If they can’t, the story is too vague.

- Small: It should be small enough to complete in a single sprint. If it takes three weeks, it’s an Epic, not a story.

- Testable: We must be able to verify that it works.

User story acceptance criteria

A user story without clear acceptance criteria is simply a guess. This is where many teams get confused, especially during handoffs between product managers and development teams.

Acceptance criteria define what “done” means. They make it easier to align expectations, write test cases, and spot edge cases early. I typically use Gherkin syntax (Given/When/Then) because it supports structured testing and maps directly to QA workflows.

You can add these criteria directly to your user story template or use a separate checklist depending on your process.

Template: “Given [Context], when [Action is carried out], then [Observable Outcome].”

Example:

- Given I am a logged-in Admin user.

- When I click “Export CSV”.

- Then a file should download to my device within 5 seconds.

Advanced templates to create user stories for different scenarios

The standard formula works for 80% of cases, but sometimes you need more specific templates.

Epic user story template and examples

Epics are larger initiatives that span multiple sprints. While user story templates focus on a single feature or goal, Epics frame the business context and help align everyone before breaking work down.

They’re especially helpful when managing complex projects with multiple dependencies or cross-functional teams working in parallel. Writing great user stories is a habit, not a one-time task. Even one story written without clear value or acceptance criteria can derail a sprint.

Format: “For [Target Audience], the [Product Name] is a [Product Category] that [Key Benefit]. Unlike [Competitor], our product [Primary Differentiator].” This helps align the team on the strategic vision before they dive into the weeds of individual stories.

For example:

- For B2B marketers, ContentPilot is a content analytics platform that shows what’s driving conversions. Unlike Google Analytics, our product ties performance to specific content types and buyer stages.

- For team leads, TaskMesh is a project planning tool that auto-prioritizes tickets based on team bandwidth. Unlike Trello, our product adjusts timelines dynamically as priorities shift.

User story template and examples for bug/product fix

Not every ticket is a new feature. Many involve diagnosing what’s broken and helping development teams fix it. For bug-related issues, a slightly different user story format, like below, helps clarify what went wrong.

Format: “As a [Role], I expect [Behavior] when I [Action], but instead [Actual Result] happened.”

This thematic user story template works well for flagging product issues without ambiguity.

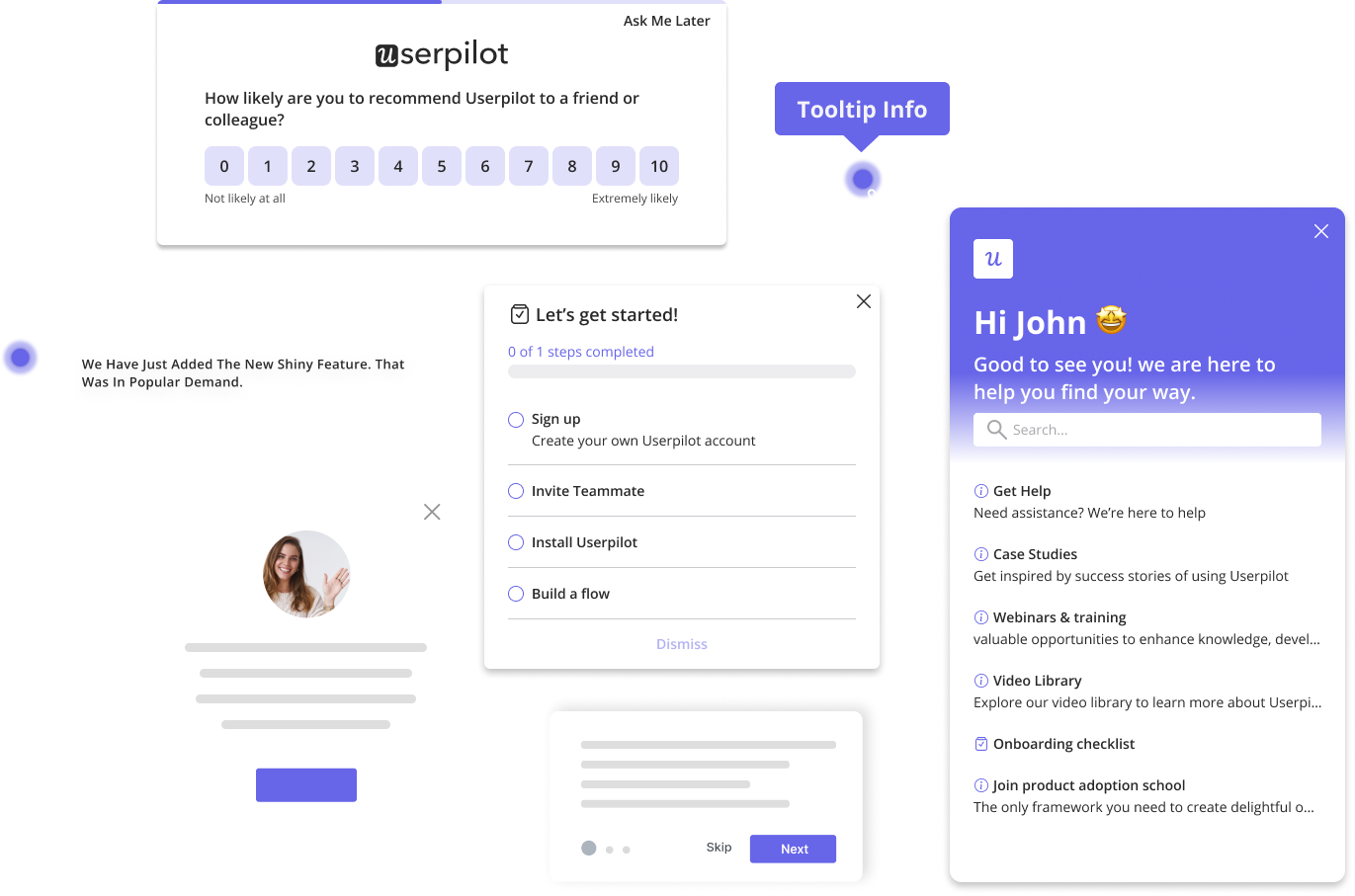

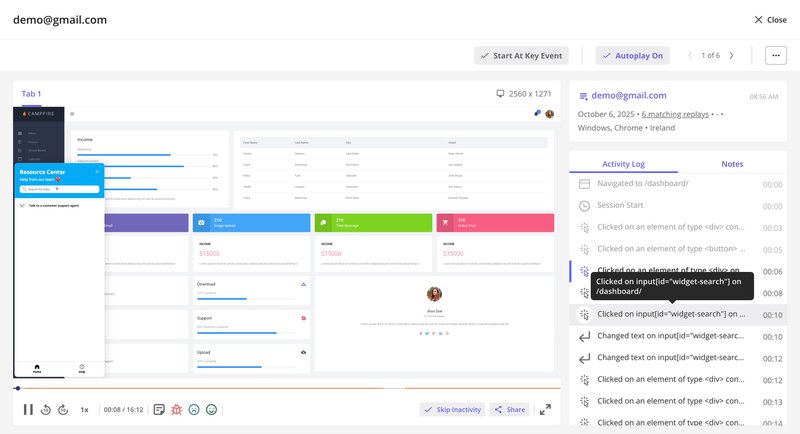

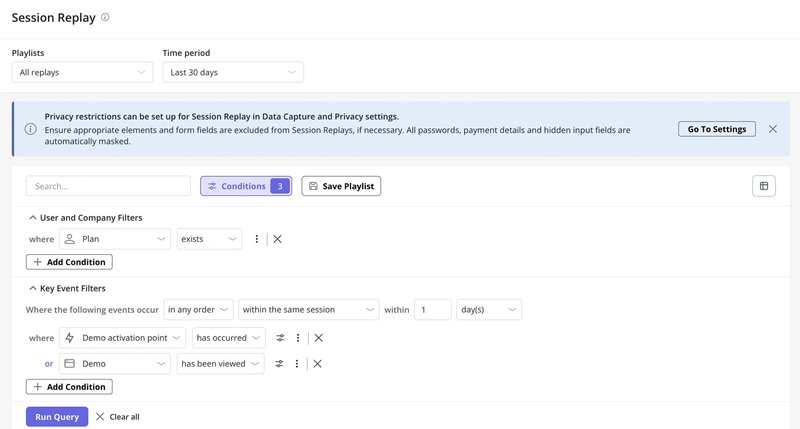

Tools like Userpilot make this easier with session replay. You can visually trace what a user did, as shown in the image below, where a user tried using the dashboard search bar but hit a dead end.

Then it’s easy to get a shareable link of that replay to add directly to the ticket so both product and engineering teams have shared context. This supports faster fixes and smoother team collaboration. This supports faster fixes and smoother team collaboration.

Examples:

- As a workspace admin, I expect the search bar to return results when I enter a keyword, but it instead shows a blank screen with no error message.

- As a customer, I expect my uploaded image to appear in the preview box, but instead, the screen shows a loading spinner endlessly.

This structure works well across bug reports and product issues. You can even include it in your user story mapping process to help with organizing user stories in sprints.

How to write better user stories using product data

The biggest mistake I see product teams make is guessing what users want. You don’t need to guess. You have data. I use Userpilot to gather the evidence I need to write compelling user stories. Here is my process to write user stories.

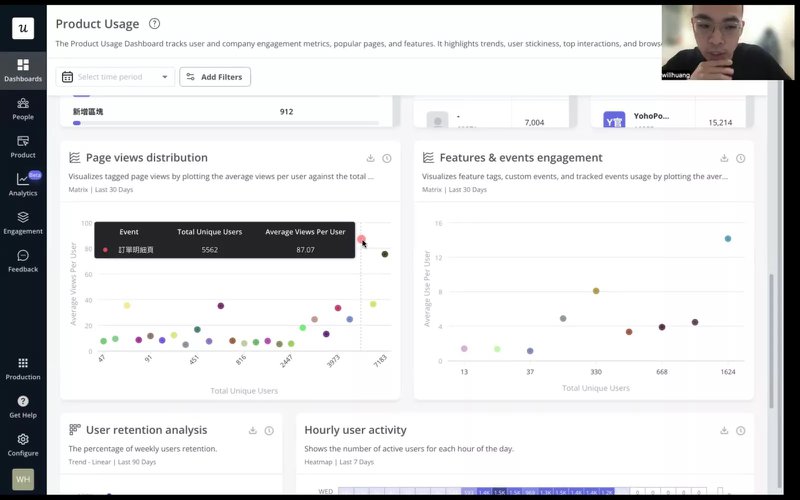

1. Identifying friction with analytics

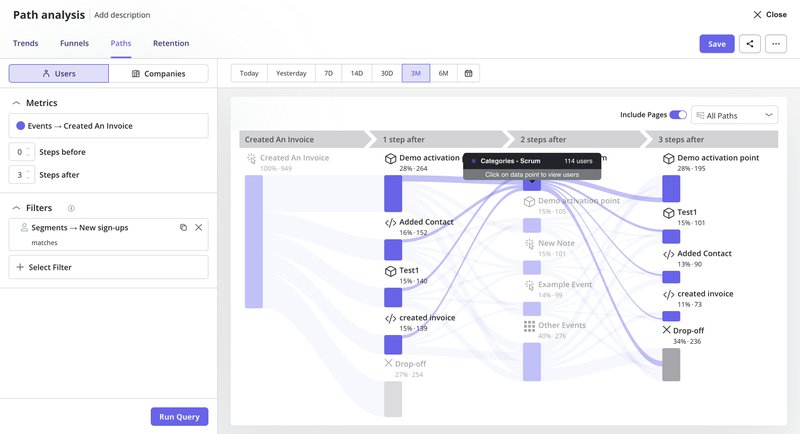

I start by looking at our Product Usage Dashboard. If I see a drop-off in a specific funnel, I know there is a problem.

For example, if users are visiting the “Reports” page but not downloading reports, I don’t only write a story to “Redesign the Reports page.” I dig deeper.

I might check Paths to see where they go instead. This data helps me write an issue-focused story, like “As a user, I want to filter reports before downloading so that I don’t have to clean data in Excel.”

That one line does more than a vague “Improve reports page” ticket. It gives the development team the why and anchors the fix in user behavior.

This exact approach helped Cleeng recover from a 92% feature usage drop after a UI redesign. With page analytics, they were able to catch the drop early.

Then the team also watched session replays to validate what was happening.

“Session replays were super useful when we changed the navigation. We could see what exactly the users were clicking and if they were visiting the pages we want them to visit.” said Anna Sobiak, Product Designer at Cleeng.

Armed with this insight, they adjusted the UI again. They replaced the hyperlink with a button and moved it to a more visible spot. As a result, usage rebounded.

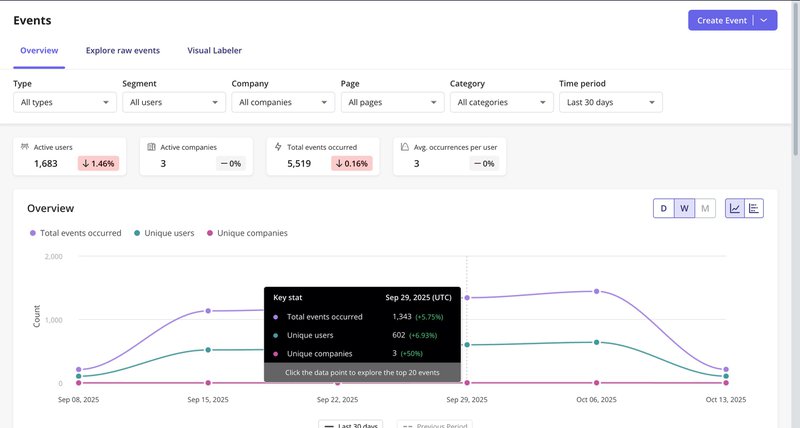

2. Tracking feature interactions for visibility

You can’t improve what you don’t measure. Before I write a story to improve a feature, I ensure we are tracking its current usage.

With Userpilot’s autocapture, I never miss any critical insights since data is collected from day one. No more waiting around for data to accumulate.

For me, having this information available from the start makes crafting compelling narratives so much easier.

If usage is low, it’s not always a functionality issue. Sometimes the problem is visibility. In that case, the story becomes: “As a user, I want to see the upload button when I’m editing a report so that I don’t miss the option to save my changes.”

You can also use this method to spot misleading patterns. Just because a page gets traffic doesn’t mean users are engaging with what’s on it.

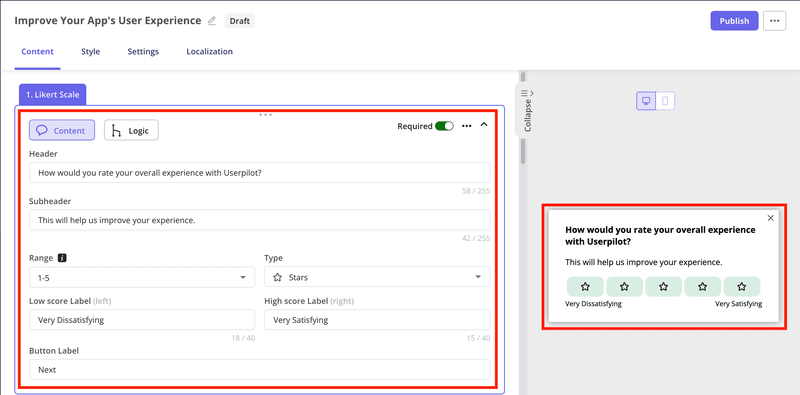

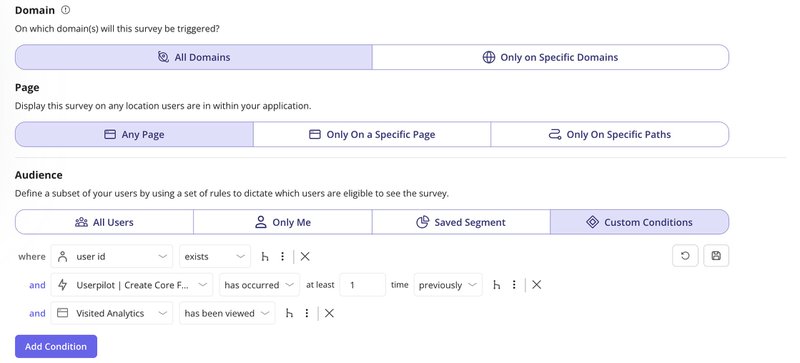

3. Gathering qualitative feedback

Quantitative data shows you what’s happening, but it won’t tell you why users get stuck. That’s where qualitative feedback helps me dig into friction points and refine the “Benefit” part of my user story with confidence.

When I’m unsure what value users are seeking from a feature, I launch a microsurvey in Userpilot.

It’s essential to determine the setup of survey logic, granular targeting, and localization to ensure the feedback comes from the exact user group I need. Say, those who interacted with a feature but didn’t complete the flow.

Open-ended questions like “What were you hoping to achieve?” or “What got in your way?” often surface blockers I didn’t anticipate.

Those insights directly shape the “So that [Benefit]” part of my user story. It’s how I make sure we’re solving meaningful user problems.

Validating the story after product release

Writing the story is only half the battle. You have to verify that it actually worked after deployment. Most teams mark a ticket as “Done” and move on. I prefer to keep the loop open until we verify the outcome.

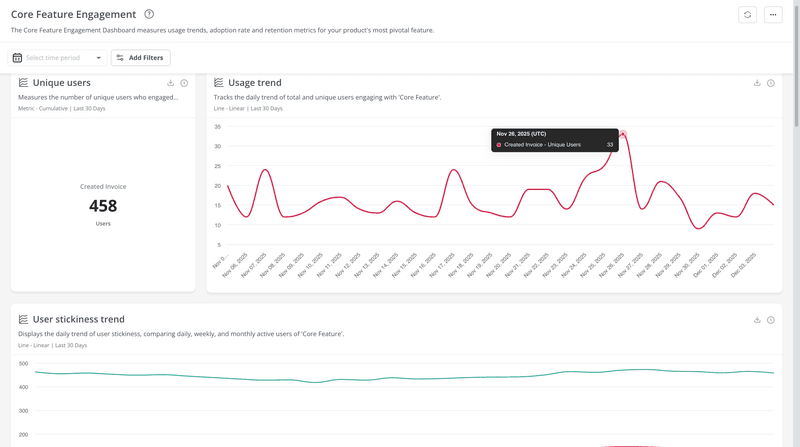

Analyzing product adoption

After a new feature goes live, I always check our core feature engagement dashboard. If the numbers don’t move, something’s off. Either the user story template didn’t reflect how users behave, or the problem it addressed wasn’t that important.

Let’s say we just shipped a new template builder. If I don’t see a steady rise in usage, I treat that as a sign to revisit the assumptions. Sometimes the feature technically works fine, but it doesn’t support how different user groups complete their workflows.

That’s why I rarely rely on a single story alone; multiple stories often emerge once I break down the flows across segments.

That happened to one of our customers, CYBERBIZ, when they redesigned their admin panel. They used Userpilot’s product analytics to track how people navigated after the update. Things like session duration and page performance helped them understand which areas reduced friction and where users dropped off. That visibility helped them improve adoption, cut down support tickets, and spot what still needed work.

“We use Userpilot to help users understand how to use the features to achieve the specific goal we want them to.”

— Wei-Di Huang, Senior Product Manager at CYBERBIZ

I’ve learned that even a well-written user story template can fall short if it doesn’t capture the desired outcome from the customer’s perspective. That’s why you should treat usage data as part of the feedback loop.

Iterating based on visual and qualitative feedback

Writing the perfect user story on paper isn’t enough, especially for new features. I rely on a mix of feedback signals to refine what we’ve shipped and spot opportunities for iteration.

If it’s a brand-new feature, I often run a closed beta with a subset of user personas. This gives me a clean space to observe real behavior without exposing untested changes to everyone.

After the feature is officially launched, I often trigger a short post-interaction survey immediately after the user engages with the feature.

Userpilot makes it easy to target specific users based on actions, and the responses I collect help validate the benefit hypothesis behind the original rollout.

If the feedback reveals that users didn’t understand the feature or couldn’t reach their desired outcome, that’s a strong signal that the story needs another round of iteration.

But I don’t rely on feedback data alone. I also watch session replays by filtering for people who’ve used the feature and watching how it fits into their workflow. All of this feeds into iteration.

Practical checklist for your next sprint

Writing great user stories is a habit, not a one-time task. Even one story written without clear value or acceptance criteria can derail a sprint.

So here is the checklist I use during backlog grooming:

- Check the persona: Did I specify a role (e.g., Admin, Editor) or just “User”? Check your User Profiles if you aren’t sure who uses the feature.

- Verify the value: Does the “So that” clause describe a real business or user benefit?

- Define done: Are there clear acceptance criteria using Given/When/Then?

- Check dependencies: Is this story independent, or does it block others?

- Size it right: Can this be done in one sprint? If not, break it down.

The goal isn’t to write perfect documentation. The goal is to build a shared understanding. When you write clear, data-backed user stories, you stop fighting with your developers and start building products that people actually want to use.

Write effective user stories with data!

If you’ve made it this far, you already know a user story template isn’t what makes a team successful. The impact comes from the thinking behind it, like understanding what users are trying to do, how they move through the product, and where the story fits in their day‑to‑day workflow.

Good user stories grow stronger every time you validate, refine, and connect them back to the customer’s perspective.

That’s why I keep Userpilot close to my process. It gives me the visibility I need to check whether a story worked, update the story template when needed, and adjust the flow when agile teams find new signals. Whether I’m reviewing a simple user story template or testing a new feature, the mix of analytics, surveys, and session replays helps me see what the next iteration should look like.

If you’re ready to stop guessing and start writing user stories that move the needle, book a demo with Userpilot today.