Feature flags are controversial.

In 2012, Knight Capital Group, a financial services firm, lost $440 million in 45 minutes due to a faulty code deployment. They went bankrupt shortly after. All that happened because of a deployment error involving dead feature code hidden behind a feature flag that was repurposed without proper flag cleanup.

I mention this not to scare you away from feature flags, but to set the stage.

Feature flags (or feature toggles) are one of the most powerful tools in modern software development. They allow teams to modify system behavior without ever touching the production server or interrupting the deployment pipeline. However, they should always be part of a deliberate release strategy, supported by solid product analytics.

With that in mind, let me walk you through what feature flags are, why top teams depend on them, and how you can use feature flags to release features with confidence.

Try Userpilot Now

See Why 1,000+ Teams Choose Userpilot

What is a feature flag?

At its core, a feature flag (also called a feature toggle or feature switch) is a software development technique that wraps a specific block of source code in conditional logic, usually simple if–else statements.

It allows you to turn functionality on or off during runtime, without deploying new code.

This simple concept allows you to ship code to your production environment that stays dormant until you are ready to activate it. You can turn it on for yourself, for your QA team, or for 1% of your entire user base.

In other words, feature flags determine which features are visible, and to whom, without requiring new deployments or risky re-deploys.

While developers often manage these flags via configuration files or databases, modern product teams use a feature flag service or feature management platform that provides a visual interface.

This allows non-technical team members like product managers or designers to control features visible to individual users or specific users without touching the codebase or introducing merge conflicts.

Different types of flags

You need to understand that not all flags are the same. If you treat a permanent permission toggle the same way you treat a temporary release flag, you will create a maintenance nightmare.

At a high level, feature flags range from blunt on off switches to more nuanced feature flippers that react to user context and system conditions. Confusing these use cases is one of the fastest ways to accumulate flag debt.

1. Feature release toggles

These are what I described above. They exist to separate deployment from release, especially in teams practicing continuous delivery or continuous deployment. They are temporary.

Once the feature is successfully launched to 100% of the user base and is stable, this new feature flag should be removed as part of normal feature flag management.

If you leave it in, it becomes technical debt.

2. Feature experiment toggles

These toggles help you evaluate whether a specific feature change actually improves a workflow. For example, you might introduce a new inline action that lets users complete a task in one click instead of moving through multiple screens.

With a feature experiment toggle, you expose this change to 50% of users while the rest continue using the existing flow. You then compare completion rates, time to complete, or downstream user engagement.

These toggles exist solely for feature flag evaluation. They live only for the duration of the experiment (usually a few weeks) and are then removed when a decision is made.

3. Permission toggles

These are long-lived. They control which multiple feature sets are visible based on user attributes such as plan, role, or contract terms.

For example, our Enterprise users might see advanced analytics features that are hidden from Starter plans. This isn’t a “rollout”; it’s a toggle configuration tied directly to pricing and entitlements, often implemented through precise user targeting rather than percentage rollouts.

4. Ops feature toggles (Kill switches)

These are safety valves for your development team. If a third-party integration starts timing out or a resource-intensive query starts causing heavy load, the engineering team can flip an Ops Toggle to disable just that specific feature, keeping the rest of the app alive.

These toggles often sit at critical toggle points in the system, sometimes routed through a central toggle router so they can be evaluated quickly under pressure. Because they protect system stability, ops toggles are often permanent and carefully monitored through flag usage data.

When feature flag implementation does make sense

I don’t think you should “flag everything just in case.” That’s how you end up in toggle hell. But there are situations where feature flags are one of the most powerful tools you have as a PM.

The first thing you should consider is team size. When you work at a larger organization with 40–100+ developers spreading across multiple teams and services, feature flags can greatly reduce friction in the development process, especially when teams practice trunk-based development instead of long-lived feature branches.

You almost certainly need flags when:

- Many of your developer squads are working on a shared platform and shipping changes in parallel through continuous integration.

- You are deploying code frequently and can’t afford to halt releases because one feature is risky.

- Your company runs a multi-tenant B2B and needs precise targeting to expose different feature sets to different customers at different times.

What feature flags are doing for you here:

- Decouple deployment from release: Code can ship any time; features go live when the product says so.

- Control blast radius: If a feature misbehaves, you can turn it off per region, customer, or test environment.

- Support complex rollouts: Different percentages by region, customer, or traffic slice, evaluated in the right toggle context.

Nevertheless, you either have a disciplined feature flag setup or a complete mess at this point.

In addition, regardless of team size, I also see feature flags become necessary when:

- Your product team is working on a critical flow (billing, auth, payments) and wants a kill switch.

- You ship to environments that are hard to roll back (mobile, hardware, regulated platforms).

- Testing UX changes with real users is a requirement, but you don’t want to manage forks across multiple languages or duplicate release logic.

- You care about gradual rollouts and not just “big bang” feature releases.

When feature flag implementation doesn’t make sense

On the other hand, feature flags are often overkill when:

- You deploy rarely and have a solid staging environment or test environment for validation.

- You’re a very small team working on an early MVP.

- The change is small, reversible, and low risk (copy tweaks, minor layout changes, small refactors).

- You’re really dealing with long-term configuration (regions, subscription entitlements, permissions) rather than temporary rollout.

In those situations, a simple config setting, environment variable, or release branch creates less complexity than a third-party solution designed for large-scale flag orchestration.

Therefore, what I’d recommend you do is to always ask yourself these 3 questions before going for any feature flag platform:

- How many people are shipping into this codebase at once?

- How often do you deploy, and how painful is rollback?

- Is this behavior temporary, or will it become a permanent flag data you’ll have to maintain?

5 Steps for implementing feature flags

Before you jump into tools or build systems, you need a super clear process. Here are five steps that I see teams use to implement flags in a way that keeps your team productive and your releases predictable:

Step 1: Be honest about what you need

The thing about feature flags is that they serve five different purposes, and most teams confuse them.

As I already mentioned above, you only need feature flags for the following situations:

- Merging code to main without showing it to users yet.

- Rolling out gradually (10% of users, then 50%, then 100%).

- Having a kill switch if something breaks.

- Running A/B tests with analytics.

- Turning features on/off for specific customer tiers.

However, most of the time, we only needed the first and third ones. You probably do too.

How we approach feature testing at Userpilot

There’s also a misconception that feature flags are the only way to test new features on real users. They’re not. Sometimes you need very specific, hand-selected participants, not a random 10% bucket.

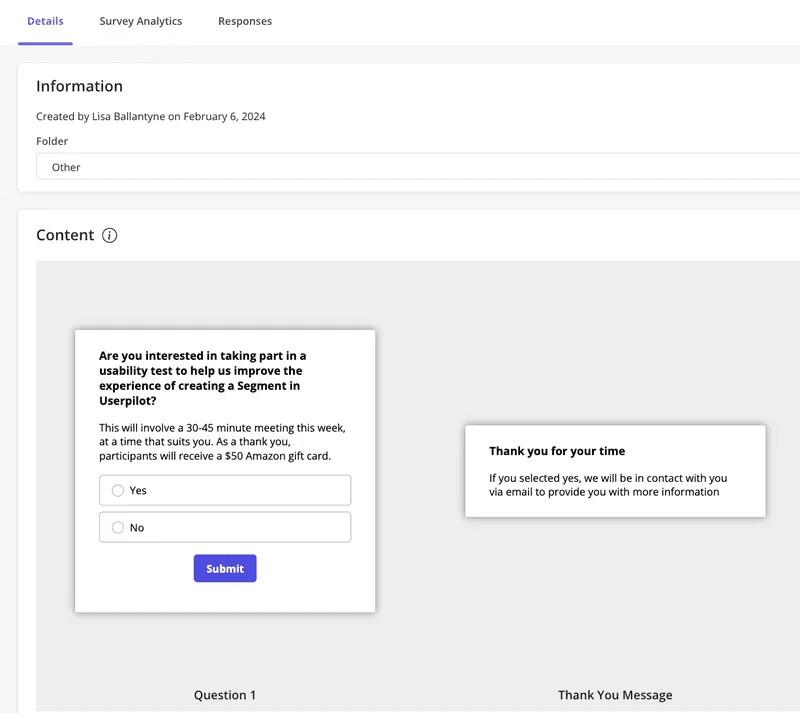

For example, in one of our projects, our UX researcher Lisa recruited highly targeted users to test a sensitive feature change before we rolled it out. When recruiting participants via email didn’t work, she used Userpilot’s in-app surveys to invite users who had already interacted with the relevant feature.

The result is surprisingly good! Lisa was able to recruit several qualified participants in just a few days.

This allowed the team to observe real usage, gather contextual feedback, and iterate confidently before rolling the change out more broadly.

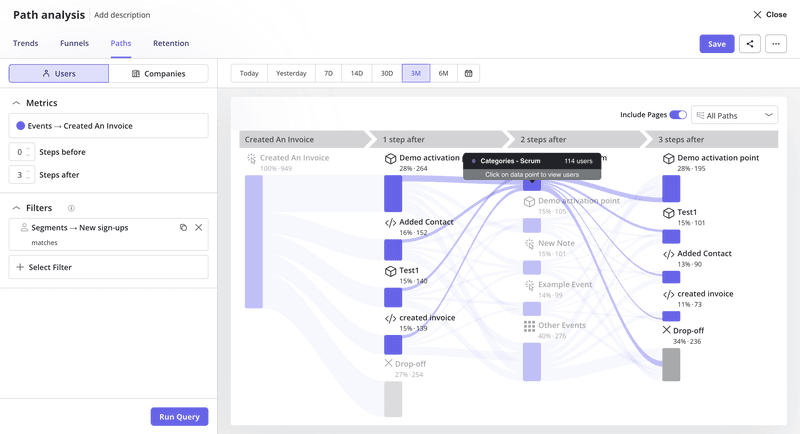

Userpilot also made it easy to track how users interacted with the new flow using behavioral analytics like paths, funnels, and trends, without relying on random rollouts or exposing unfinished work to the wrong users.

If we used feature flags alone, we’d have exposed the update to random people with none of the context we needed. Instead, we intentionally controlled who saw the feature because the research required intentional sampling, not random sampling.

This is why I always tell teams: Feature flags are a release tool, not your entire research strategy.

And once you understand that, you also realize you don’t need a pricey tool just to flip on/off switches. Both GrowthBook and Statsig offer free entry tiers with unlimited flag capabilities and experimentation options, with paid plans available as your needs grow.

If all you need is safety and control, you can build what you need in a weekend.

Step 2: Start with a database table

We created a simple table with three things: feature name, who gets it, and whether it’s on or off.

That “who gets it” part can be:

- Everyone who is in production.

- Everyone who is in staging.

- Users with “beta_tester” status.

- Companies on the Enterprise plan.

- 25% of all users.

From my experience, if you are doing percentage rollouts, you don’t need fancy software. You can simply use this formula: If the last two digits of a user’s ID are less than 25, they’re in the 25% group.

This is even better when you mix the user ID with the feature name and scramble it (developers call this “hashing”). This prevents the same users from always being in every test group.

This works simply because all that user data, like subscription tier, beta status, or country, already lives in your database. You’re just adding if-statements around information you already have.

This is also how we’ve handled BETAs at Userpilot.

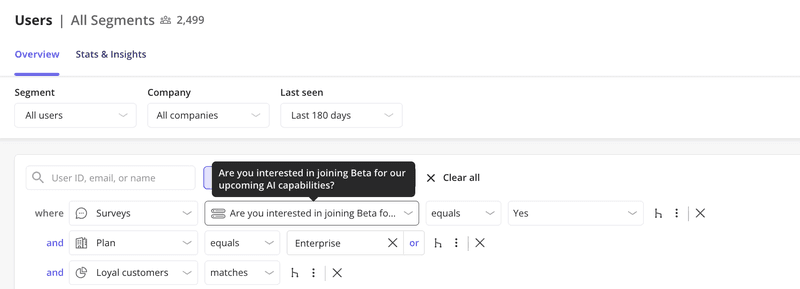

Nevertheless, we don’t use feature flags at the moment. Instead, when we release something like Session Replay in early access, we ask customers directly, usually through an in-app survey or a “Join beta” button using our own tool, Userpilot.

Anyone who opts in gets a property on their company record, such as Has Emails BETA = true, and that single value determines whether the feature appears for them.

Step 3: Use Redis or any storage you can change without restarting

This was our breakthrough moment.

If you use config files or environment variables, you have to rebuild and redeploy every time you change a flag. That defeats the entire purpose.

What works in this case is to put flags in Redis (think of it as a super-fast spreadsheet in the cloud). Now, when something breaks at 2 am, we can turn it off instantly. No rebuild, no deploy, no waiting.

This is the difference between “flip a switch” and “wait 20 minutes for our build pipeline.”

Step 4: Set up automatic cleanup

Remember the Knight Capital story I mentioned earlier? Knight had repurposed an old flag that used to turn on a legacy “Power Peg” function in their trading system. When they rolled out new code for the Retail Liquidity Program, one of their eight servers never got the updated version.

So when orders hit that one out-of-date server with the reused flag turned on, the old Power Peg logic woke up and started firing trades. A bug in that legacy code meant it never marked orders as complete, so it just kept sending new ones until Knight had racked up roughly $440–$460 million in losses in under an hour.

That’s what long-lived, poorly managed flags look like in the worst case: invisible code paths, nobody remembers what they do, and a single toggle melts production.

I’ve known teams who had flags that would literally crash their code if not extended or removed after a deadline. Aggressive? Yes. Effective? Also yes.

We took a softer approach but with teeth.

This is what our system looks like:

- Every flag gets an owner (a real person’s name).

- Every flag gets an expiration date (usually 2-4 weeks after feature launch).

- We review all active flags monthly.

- If a flag has been sitting there for 3+ months, it gets deleted automatically.

So in short, you only need to keep a simple document with information such as flag name, what it controls, who owns it, why it exists, and when to remove it. When someone asks, “What does this flag do?” six months later, you’ll have an answer instead of archaeology.

Step 5: Know when to stop DIYing and just pay

For most teams of around 15 or more developers, it will be the decision point.

The fork in the road happens when:

- Your product manager wants to toggle features without asking engineering.

- You need detailed analytics on which version performs better.

- Multiple teams are using flags, and you need audit logs.

- You’re managing different features for 50+ enterprise customers.

That’s when those paid services start making sense, not because the technology is hard, but because you’re buying a UI for non-technical people and automatic audit trails.

Banks with 3-week release cycles? They put everything behind toggles. High-velocity teams shipping 20+ times per day? They use simple Python libraries. AWS? Their teams just built their own.

Therefore, what you’re actually paying for is change management and analytics, not technical complexity. If you need A/B test analytics and a pretty dashboard for your marketing team, services like Statsig or GrowthBook’s paid tier make sense. Both offer free entry tiers with experimentation and flag capabilities, and paid plans scale based on usage or team size as your needs grow.

If you just need to ship code safely and sleep well at night knowing you can turn things off? Build it yourself this weekend.

Are feature flags a good idea?

I’d say yes, feature flags are a good idea. But they’re also easy to overuse.

For many teams, feature flags become either too complex to manage or too costly for what they actually need. They add overhead around configuration, monitoring, and cleanup, and without discipline, they can quickly turn into technical debt.

That’s why feature flags shouldn’t be your default tool for every rollout or experiment. In fact, for beta testing, you often don’t need feature flags at all.

At Userpilot, we take a more intentional approach. Instead of rolling features out to random percentages of users, we invite interested customers to opt in through in-app surveys or a simple “Join beta” button. Anyone who opts in is marked with a company property, which determines whether the feature appears for them.

This gives teams precise control over access and a clearer context around feedback. More importantly, it lets you observe how beta users actually interact with the feature.

Using Userpilot’s analytics, you can track user flows with path analysis, identify friction points with funnels, and review session replays to understand how the feature fits into real workflows.

So, feature flags are powerful release tools. But when learning and iteration are the goal, intent-based access and behavioral insights can often get you there faster, with far less overhead.

If you want to see how this works in practice, you can book a Userpilot demo.