MoSCoW Prioritization Explained and How I Use It for Product Management

For every product manager, it’s always a classic tug of war in UX design to decide what to build next. I’m sure you’ve been there. The sales team needs a specific feature to close a big deal, engineering is flagging technical debt, and user feedback is pulling you in another direction.

It’s no wonder that for 43% of PMs, planning and prioritization are their biggest struggle.

This is where MoSCoW prioritization helps me make better tradeoffs.

In this guide, you’ll learn how MoSCoW prioritization works and when this framework makes more sense than other methods like RICE or Kano.

I’ll also walk through real examples and mistakes I’ve seen PMs make when applying it.

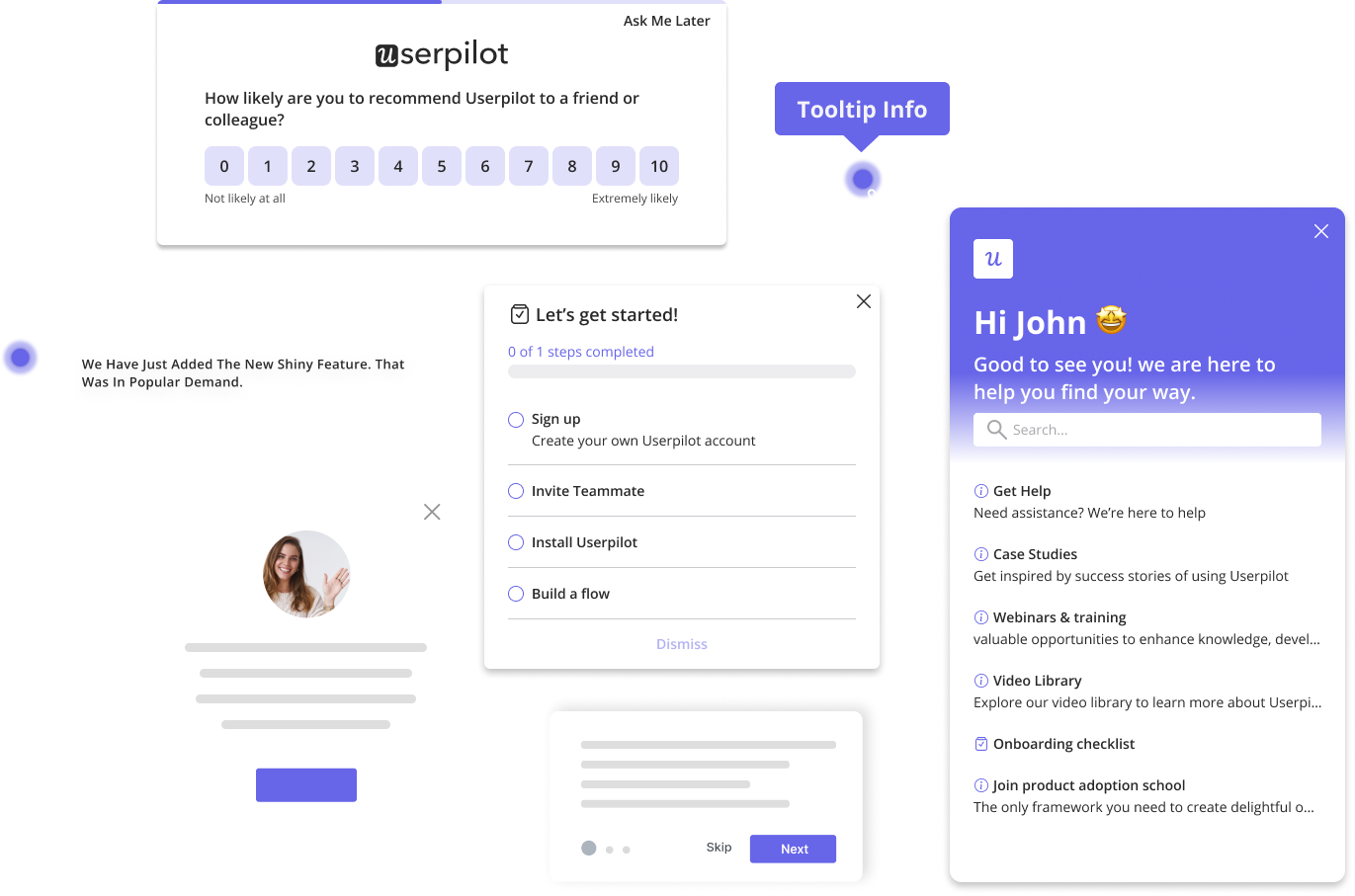

Try Userpilot Now

See Why 1,000+ Teams Choose Userpilot

What is the MoSCoW prioritization method?

MoSCoW is an acronym that stands for Must-have, Should-have, Could-have, and Won’t-have (this time). The lowercase ‘o’s are just there to make it pronounceable; they don’t stand for anything.

Developed by software expert Dai Clegg while at Oracle, the method was designed to help teams prioritize work within a fixed timeframe, a common scenario in agile development.

I think it’s a decent framework to force your team to agree on what is critical now instead of debating over feature requests.

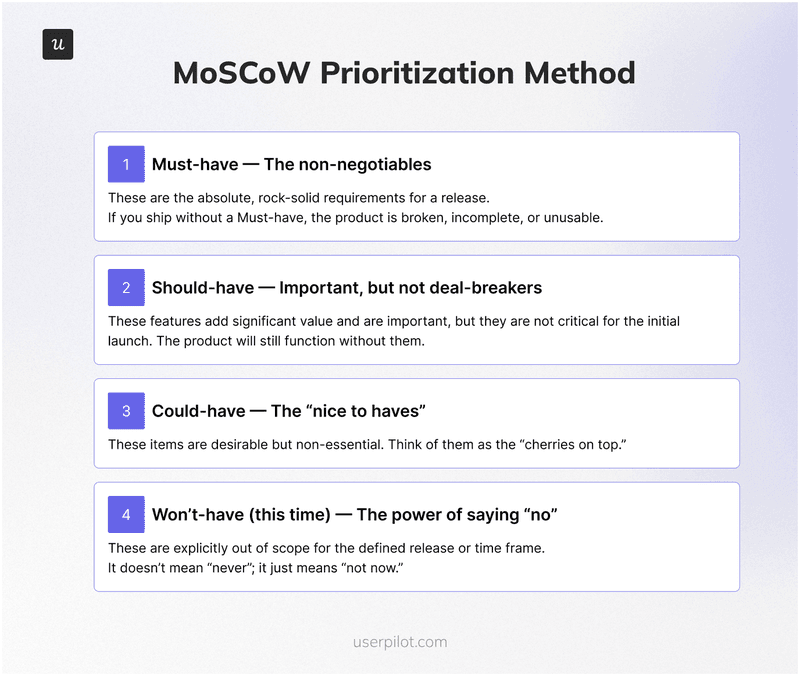

4 Categories of the MoSCow technique

What I like most about the MoSCoW prioritization method is how easily it gets everyone aligned.

The four prioritization categories (Must-have, Should-have, Could-have, and Won’t-have) help the project team get on the same page fast.

It’s a very simple framework, but it gives everyone a shared understanding of what truly matters for project success before we jump into execution.

Let’s take a closer look at each:

Must-have: The non-negotiables

These are the absolute, rock-solid requirements for a release. If you ship without a “Must-have,” the product is broken, incomplete, or useless. It might even be illegal or insecure.

When my team is debating if something is a “Must,” I ask these questions:

- If we launched without this, would the release fail to achieve its core purpose?

- Is there a legal, security, or compliance reason this must be included?

- Can the user complete their primary task without this feature?

- Is there a reasonable workaround? If the answer is no, it’s probably a “Must-have.”

For example, when building a new user login system, user registration and password recovery are “Must-haves.” The system is fundamentally broken without them.

These items form the backbone of your Minimum Viable Product (MVP) and are the first things your team should build. A poor MVP experience can create so much user friction that users never return.

Should-have: Important, but not deal-breakers

“Should-have” features are important and add significant value, but they are not critical for the initial launch. The product will still function without them. They are often the difference between a good product and a great one, but they aren’t essential for this specific release.

I think of these as the top contenders for the next development cycle. They are not as critical as “Must-haves,” but they are still high-impact.

A “Should-have” might be a performance improvement or a feature that makes a common task much easier.

For our login system example, integrating a social login option (like “Sign in with Google”) would be a “Should-have.” It adds a ton of value and convenience, but the core login system works without it. These are often features that would vastly improve the product experience for a large user segment.

Could-have: The “nice to haves”

These are the desirable but non-essential items. You can think of them as the cherries on top. They have a smaller impact on the overall product than a “Should-have” and are often the first to be dropped when timelines get tight. If you have time and resources left after completing your “Musts” and “Shoulds,” you can pick from this list.

In my experience, “Could-haves” are great for adding a bit of polish or delight. For our login system, a “Could-have” might be the option to customize the user’s profile avatar. It’s a nice touch and could boost user engagement, but its absence won’t hurt the product’s core function. Sometimes, these small additions can come from experimenting with engagement gamification techniques.

Won’t-have (this time): The power of saying ‘no’

This is the most underrated and powerful category. Placing an item here doesn’t mean it’s a bad idea or that it will never be built.

It simply means it is not a priority for this specific release or time frame. This category is crucial for managing expectations and preventing scope creep, which can derail even the best-planned projects.

Being clear about what you are not building is just as important as being clear about what you are building. The “Won’t-have” list helps keep the team focused and reassures stakeholders that their ideas have been heard, even if they aren’t being acted on right now.

We often move items from here into the backlog for future consideration, ensuring we don’t lose good ideas. It’s a key part of maintaining a healthy and actionable friction log over time.

How I implement MoSCoW method to prioritize tasks

Most experienced PMs I know don’t rely on a single prioritization method. In fact, product managers mix and match different prioritization techniques. For example, RICE for estimating how much effort something takes, Kano for understanding user delight, and sometimes no formal framework at all when project execution is moving fast.

I prefer the MoSCoW prioritization method when we have the space to slow down, involve key stakeholders, and walk through each phase properly.

When I need a broader perspective for an entire project, or we’re planning future releases with tight deadlines and limited resources, MoSCoW might not be the one you should look at.

But of course, a MoSCoW analysis isn’t something I do alone at my desk. Its effectiveness comes from collaboration. Here’s a simple step-by-step process I follow with my team to ensure we get the most out of it:

Step 1: Align your development team on objectives first

Before we even talk about features, we make sure everyone in the room agrees on the goal of the project or release.

Are we trying to increase user acquisition, improve retention, or enter a new market? Without team alignment, everyone will prioritize based on their own agenda. Linking our work to a clear value-based growth strategy gives us a north star.

Step 2: List everything out

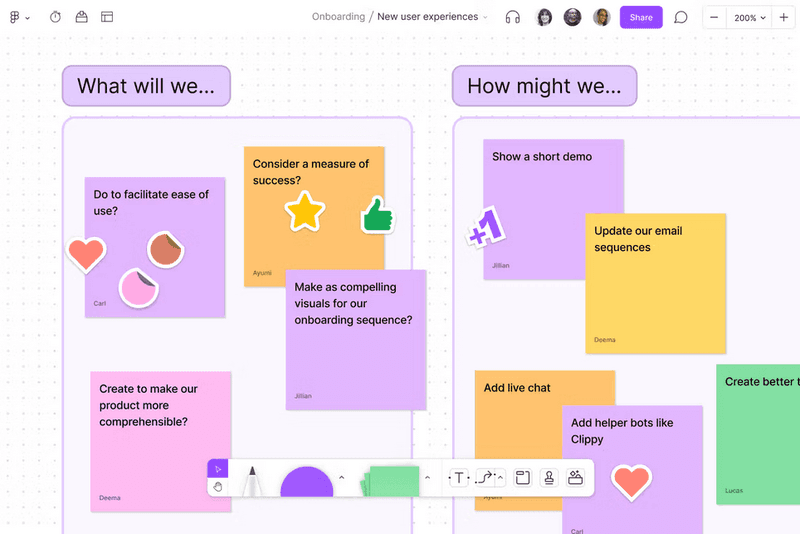

We gather all desired features, requirements, bug fixes, and ideas from all stakeholders: product, engineering, design, marketing, and sales.

We use a shared document or whiteboard and get everything out in the open. No idea is too small or too big at this stage. We even pull from recent customer service survey results.

I’ve found this step works best when you make it easy for project team members to pitch in asynchronously. Tools like FigJam, Notion AI, or even Miro help you visualize priorities early and capture project elements you might otherwise forget.

In larger software development teams, this single board can become the anchor for stakeholder communication, allowing everyone to react, comment, and clarify project requirements before jumping into the prioritization process.

It also gives the product team a clear understanding of how many essential features, critical elements, and less critical tasks are in play before we use the MoSCoW prioritization technique to sort them.

Step 3: Get everyone on a categorization session

This is the core of the session. We go through the list item by item, discuss, and negotiate where it belongs.

The sales team might argue a feature is a “Must-have” to close a deal, while engineering might explain the technical complexity makes it a “Could-have” at best for this release.

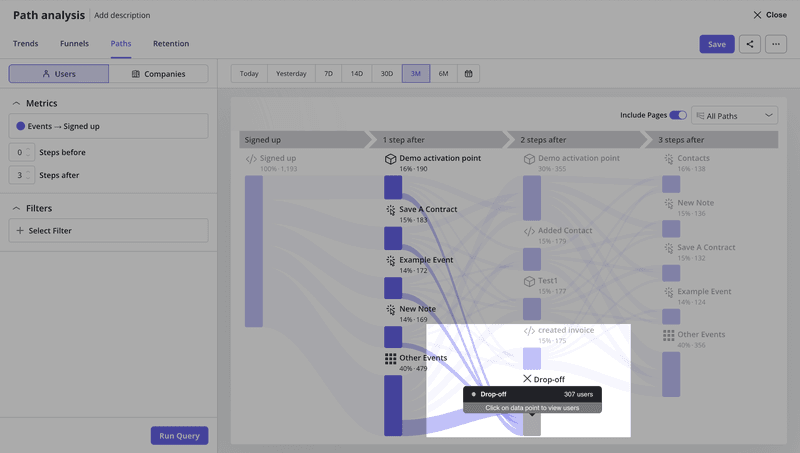

This is where data tracking and insights from behavior analytics tools become your best friend, turning subjective opinions into evidence-based decisions.

For example, if one customer says your interface is confusing, it’s tempting to categorize that as a Must-have fix.

But before the team prioritizes tasks around it, I’ll jump into Userpilot to check path drop-offs, repeated rage-clicks, or NPS follow-up comments to confirm whether it’s an isolated complaint or a pattern across user segments.

Sometimes the data shows a genuine blocker. Other times it’s a nice-to-have feature that can wait until resources permit.

You see a clear example of this in the Zoezi case study. Their team used to rely heavily on feedback from their most vocal customers, which skewed their decision-making.

Once they adopted Userpilot, they finally had visibility into how the broader user base navigated the product: which pages they visited, where they got stuck, and what they completely ignored.

We were in a pretty bad state before Userpilot because we didn’t even know what pages people visited. Now we can just look at the pages tab and understand that people don’t use this stuff, so let’s not focus on that.

– Isa Olsson, UX Researcher and Designer at Zoezi

That’s exactly how the term MoSCoW starts making sense in practice: a straightforward framework supported by real-time behavior data. It helps teams focus, improves stakeholder management, and makes it easier to adjust priorities without unnecessary debate.

Step 4: Set resource limits

To avoid the trap of everything becoming a “Must-have,” we set rough resource allocations. A common rule of thumb is that “Must-haves” should not take up more than 60% of the team’s effort for the release.

This forces us to be realistic and leaves contingency for “Should-haves” and “Could-haves.” It ensures we’re building a balanced release and not just the bare minimum.

Step 5: Communicate and revisit

The output of the session is a prioritized list that we share across the organization. This transparency manages expectations. But priorities can change.

We revisit our MoSCoW list regularly, especially at the start of a new sprint or when new information comes to light. This isn’t a “set it and forget it” exercise.

The common pitfalls I’ve learned to avoid

MoSCoW is simple, but that doesn’t mean it’s foolproof. I’ve seen teams make mistakes that undermine its effectiveness. Here are the biggest ones to watch out for:

The “Everything is a must-have” trap

This is the most common pitfall. When every stakeholder believes their request is critical, the “Must-have” list becomes bloated and unrealistic.

This defeats the whole purpose of prioritization. The 60% resource allocation rule I mentioned is the best defense against this. It forces a conversation about trade-offs. If a new item is added to “Must-have,” something else may have to move out.

Subjectivity and bias

Without objective criteria, categorization can become a battle of opinions. The loudest voice in the room often wins.

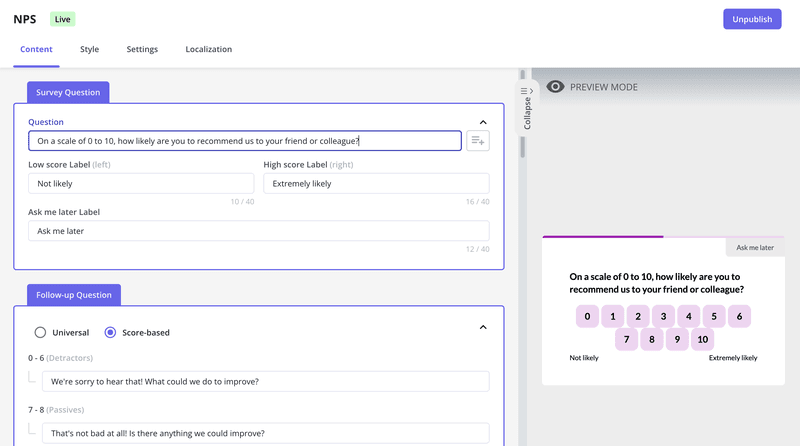

To counter this, we ground our decisions in data. We use product usage analytics to see what features people actually use, and we gather qualitative feedback through tools like in-app NPS surveys. You can also build an effective NPS survey template to make this easier.

The more I work with cross-functional teams, the more I’ve seen how quickly bias shows up in MoSCoW sessions. Sales pushes for revenue-driven items, engineering leans toward technical debt, and design goes for UX improvements.

That’s why I rely heavily on Userpilot during this stage, because it helps balance opinions with real behavioral evidence.

Instead of debating whether something is one of the critical features, we check actual engagement, drop-off paths, and NPS follow-up patterns to understand its impact on users.

This is also where Userpilot’s upcoming AI features will make MoSCoW prioritization even faster.

You’ll be able to chat with an assistant that instantly summarizes NPS themes, highlights friction points, or flags unusual behavioral clusters across segments.

Instead of digging through charts, the AI surfaces insights you can bring straight into the categorization room.

👉 If you’d like to know more, you can join the beta here.

When someone says a feature is a “Must,” we ask for the data or user feedback that supports that claim. This is a core part of creating excellent SaaS experiences; you have to know what matters to the user.

Forgetting to involve the whole team

Prioritization done in a silo is doomed to fail. If you don’t include engineering in the discussion, you might classify a feature as a “Must-have” without realizing it will take six months to build.

Involving cross-functional teams from the start, including design, engineering, marketing, and customer support, ensures that decisions are realistic and everyone is bought into the plan.

How MoSCoW analysis compares to other prioritization techniques

When I look at how different prioritization frameworks work in real life, I’ve noticed the MoSCoW prioritization technique sits in a very different place compared to scoring models like RICE or user-delight tools like Kano.

Here’s a simple side-by-side comparison to show how each framework approaches prioritization:

| Method | Best for | How it works | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| MoSCoW | High-level alignment, quick sorting of critical features for a product release | Categorizes work into four MoSCoW categories: Must-have, Should-have, Could-have, Will-not-have | Can be subjective, no scoring, not ideal when juggling many projects |

| RICE | Quantifying impact when you need to justify prioritization | Scores features by Reach × Impact × Confidence ÷ Effort | Requires good data, harder for new products, doesn’t highlight user delight |

| Kano | Understanding how features affect satisfaction and UX sentiment | Classifies features as Basic, Performance, and Delighters | Doesn’t factor business objectives or task prioritization effort; best paired with another framework |

If you spend any time in PM communities, you’ll see that most PMs rarely use MoSCoW as their primary framework. RICE and Kano show up far more often because they support scoring, effort modeling, and customer-centric thinking.

MoSCoW still has its place, especially in teams running an agile project management method, where you need a fast way to group work or communicate what will not fit in a sprint.

But as many PMs say, MoSCoW can feel too broad and too tied to its very simple principles, which don’t always help with complex roadmap planning or negotiation across large organizations.

Here are a few cases where I think MoSCoW just isn’t the best fit:

- Too subjective: Without a scoring model, Must vs. Should debates drag on and depend heavily on who’s in the room?

- Doesn’t scale well: When you’re managing complex roadmaps or multiple projects, MoSCoW doesn’t give you enough structure to compare trade-offs.

- Ignores effort modeling: You can’t capture how much effort something takes, which is a major blind spot during sprint planning or long-term strategy work.

- Not ideal for long-term strategy. It’s great for early sorting, but not strong enough to guide detailed software development decisions or sequencing.

Honestly, I don’t know a single PM who uses one prioritization framework exactly the way the textbook describes it. We all mix things, adapt, or steal pieces from different models depending on the team, company, or type of project we’re working on.

Personally, I use MoSCoW when I need alignment fast, especially when we’re trying to get everyone on the same page early in planning. It does help calm the chaos down and get conversations started. But once we’re past that point, I’ll usually add in more structured methods like RICE or Kano to make smarter trade-offs.

Validate your MoSCoW priorities with real user data!

Truth is, even the best MoSCoW plan falls apart without real usage insights behind it. So before you commit to a Must-have or push something into future releases, make sure your decisions reflect how users actually behave, not just how you think they behave.

That’s where tools like Userpilot make the whole process easier. You can validate assumptions, check engagement patterns, and refine your MoSCoW buckets with confidence. To see how Userpilot can help you prioritize smarter, book a Userpilot demo.

![10 Free Product Roadmap Templates You Need in 2026 [+Free Download] cover](https://blog-static.userpilot.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/10-product-roadmap-templates-you-need-in-2026-free-download_d8269f0b0b9749f6ad7b519ab7ac1833_2000-1024x670.png)